Translate this page into:

Diabetic nephropathy – Epidemiology in Asia and the current state of treatment

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Historical Remarks

Type 2 diabetes is by no means a novel disease. No definite description of diabetes can be found in the Corpus Hippocraticum or in the subsequent European literature, except inconclusive descriptions by Galenus and Aretaios. It took centuries before the sweet taste of urine in diabetes was described by Thomas Willis (in 1674) and sugar in the urine was identified by Matthew Dobson (in 1776). In contrast, a large body of evidence points to the common presence and diagnosis of diabetes in ancient India and China, presumably the result of genetics and lifestyle – and acumen of the respective physicians.

The characteristic sweet urine in diabetes was mentioned in the Indian Sanskrit medicine literature[1] presumably written between 300 before and 600 after Chr. The ancient physicians described “sugar cane urine” (Iksumeha) or “honey urine” (Madhumeha and Hastimeha) as well as “urine flow like elephant in heat”; furthermore, they mentioned the observation that ants and insects rush to this type of urine – suggesting that the observations concerned true glucosuria and diabetes.[1] The ancient Indian physicians ascribed this condition to excessive food intake and insufficient exercise; they also mentioned the complete list of the three cardinal symptoms: polyphagia, polyuria and polydispsia; even secondary sequelae of diabetes such as abscess formation, carbuncles, lassitude and floppiness were reported. Suggested interventions ranged from administration of honey and sugar in patients with Iksumeha and Mathumeha (illogical, but possibly envisaged as substitution therapy) to the (very rational) advice of active physical exercise with long marches and riding on elephants [Schadtewaldt H., Geschichte des Diabetes Mellitus (History of Diabetes Mellitus), Springer, Berlin-Heidelberg-New York 1975].

In China, the earliest description of diabetes as “xiao-ke” (wasting thirst or emaciation and thirst) syndrome can be traced back more than 2000 years ago to the Yellow Emperor's Classic of Medicine (Huangdi Neijing) [Deng, Y.Y. and Y.P. Chen, Diabetic nephropathy. In: Wang G., Y.P. Chen and Y.Q. Zou, eds. Contemporary nephrology in traditional Chinese medicine (p.585-602). Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2003 (in Chinese)]. Ancient Chinese physicians had noted that « sweet » urine was a manifestation of this disease, which was further classified into upper (characterized by thirst and polydipsia), middle (characterized by hunger and polyphagia) and lower (characterized by thirst and polyuria) subtypes based on different manifestations [Shen, Q.F. (ed), Clinical nephrology in traditional Chinese medicine. Shanghai: Shanghai Scientific and Technological Literature Publishing house, 1997 (in Chinese)]. In addition, the ancient Chinese literature documented the complications of xiao-ke (e.g., skin abscesses, infections, blindness, turbid urine and edema) and ascribed its pathogenesis to improper fatty, sweet and rich diet, emotional imbalance and physical or sexual overindulgence (Liu Z.W., Liu L.(eds)Essentials of Chinese Medicine, New York, Springer 2009). Diet therapy, exercise, herbal medicine and acupuncture were proposed by ancient Chinese physicians centuries ago [Gao Y.B.(ed.) Ancient and contemporary case reports on diabetes mellitus. Beijing, The people's Military Medical Press, (2005) (Chinese)].

These observations, relatively specific and strong in India, but also very suggestive in China, indicate that diabetes had been known in Asia for a long time.

Epidemiology

Against this long historical background, what is new is the recent steep rise in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome[2] and of type 2 diabetes[3] worldwide, which is extremely pronounced in Asian countries,[3] and is particularly dramatic in India.[4–6] This gave India the dubious distinction of the “diabetes capital of the world.”[7] Indian diabetic patients tend to have pronounced insulin resistance, higher waist circumference despite lower body mass index as well as lower adiponectin and higher inflammatory markers.[7] A high prevalence of the precursors of diabetes, i.e. of the metabolic syndrome[28] and of glucose intolerance,[9] has been well documented in the Indian population. As everywhere, the prevalence of overt diabetes is particularly high in Indian elderly[10] – but of great concern is the frequency of obesity,[11] of prediabetes and of overt diabetes in the young.[612] Diabetes is also particularly frequent in the rural populations of India.[13–15] In parallel with the increase in diabetes, a dramatic increase in the prevalence of diabetic nephropathy has been noted,[1617] which has become the single most common cause of end-stage kidney disease according to some,[1819] but not all,[20] reports. In the elderly, diabetic nephropathy today accounts for no less than 46% of chronic kidney disease.[21] In the “Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study,” the prevalence of overt nephropathy and microalbuminuria was 2.2% and 26.9%, respectively, in the urban citizens with diabetes,[22] There are indications (as also observed in our cohort in Heidelberg[23] ) that the presence of diabetes increases the risk of, and presumably also the rate of progression, of nondiabetic kidney disease.[24] The estimated overall incidence rate of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in India is currently 800 per million population and 150–200 pmp, respectively.[17]

Of great interest is the fact that compared with the local populations of European origin, in citizens of a South-East Asian origin, the risks of impaired fasting glucose and of impaired glucose tolerance are markedly higher.[25] Furthermore, the prevalence of any type of chronic kidney disease and its rate of progression, but specifically also of diabetic nephropathy, is significantly higher in citizens of Asian origin, as observed both in the UK[26] and in Canada[27] – presumably the result of different genetics and/or lifestyle. In these communities, there is a lack of awareness of kidney complications despite familiarity with diabetes – an educational challenge.[28]

The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified diabetes as a major health problem in Asia and, in this context, prevention of diabetes has become a high priority of health policies.[329]

The root of the problem is the current lifestyle causing visceral obesity; the long-term solution must be changes in lifestyle.[33031] Disappointingly, a recent 6-year lifestyle intervention study while improving the risk of retinopathy failed to improv[e the risk of nephropathy,[31] but interventions of longer duration may be necessary – illustrating the magnitude of the problem.

Nevertheless, the dramatic increase of advanced diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes requires additional measures targeted more specifically to the kidney. The prevalence of diabetic nephropathy is aggravated by today's decreased cardiovascular mortality of diabetic individuals so that ever more patients reach the stage of advanced nephropathy. Fortunately, in the recent years – apart from better metabolic control of diabetes – specific nephroprotective interventions have become available.

Diabetic Nephropathy

Until the 19th century, type 2 diabetes was relatively infrequent in Europe and elsewhere. With increasing wealth and increasing prevalence of obesity, a progressive increase in the frequency of type 2 diabetes was noted. Proteinuria in type 2 diabetes had been well known in the 19th century, but ESRD in type 2 diabetic patients was relatively uncommon because most patients died of cardiovascular events or other, mostly infectious, complications. Diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes emerged relatively late as an issue.

Epidemiology of end-stage renal disease

Today, ESRD has become very rare in type 1 diabetes. ESRD was, for a long time, not a major problem in type 2 diabetes. In the 1980s, however, when past restrictions to accept type 2 diabetics for dialysis were relaxed, admission of type 2 diabetic patients for dialysis increased dramatically; we called this “a medical catastrophe of worldwide dimensions.”[32] In the ‘90s and in the early years of the first decade after 2000, the rate of admission of type 2 diabetics for dialysis continued to increase. More recently, however, the admission rate has stabilized in the US (USRDS Registry www.usrds.org/adr.htm) as well as in Europe.[33] Observations in the Pima Indians, an Indian tribe in the USA with a particularly high prevalence of type 2 diabetes, suggest that such stabilization of admission rates is not explained by higher rates of cardiovascular death prior to ESRD, but reflects a real decrease – presumably the result of effective intervention (interestingly, if anything, the incidence of proteinuria has increased).[34]

Today, however, the classical presentation of Kimmestiel-Wilson's disease is no longer the only mode of presentation of ESRD in all type 2 diabetic patients. In our own series,[23] we found

-

classical Kimmestiel-Wilson (i.e., enlarged kidneys, heavy proteinuria with and without retinopathy) in 60%,

-

ischemic nephropathy (i.e., shrunken kidneys, modest or no proteinuria) in 13% and

-

primary kidney disease with superimposed diabetes in 27%.

It is therefore important not to automatically diagnose diabetic nephropathy in all type 2 diabetic patients with ESRD but to take a careful history, to examine the urinary sediment, etc. to exclude other renal diseases.

Our observation that a certain proportion of type 2 diabetic patients with ESRD have little or no proteinuria is in line with many recent reports that a sizable proportion of diabetic patients with reduced eGFR has no albuminuria.[35] In the UKPDS study, after 15 years of follow-up, 28% had developed an eGFR <60 ml/min and 14% had no albuminuria;[36] similar data were reported from the US.[37] A recent 7.5-year prospective study showed that the presence of cerebral microinfarcts, documented by brain magnetic resonance imaging, predicted subsequent doubling of serum creatinine or dialysis dependency in diabetic patients with no microalbuminuria[38] – suggesting that this nonproteinuric type of renal malfunction is the result of arteriolopathy.

More recently, we have seen with increasing frequency type 2 diabetic patients presenting with further modes of terminal renal failure. Type 2 diabetic patients with CKD are much more prone to develop superimposed acute kidney injury (AKI) (“acute on chronic kidney disease”), often triggered by infections, administration of radiocontrast, hypovolemia, etc. AKI in type 2 diabetic patients is associated with a high mortality. In a certain proportion of patients, the AKI is irreversible. Patients who recover from AKI subsequently exhibit frequently delayed progression to terminal renal failure[39] so that follow-up controls are obligatory.

Another important point is that in our series, in 11% of the patients in whom the oral glucose tolerance test documented the presence of type 2 diabetes, the referring physician had been unaware of the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Interestingly, in the US Registry (USRDS) 10% or more of the patients on dialysis developed apparently de novo diabetes in the first 2 years of hemodialysis. Presumably in the preterminal stage of uremia, because of weight loss and anorexia, many patients with type 2 diabetes are no longer hyperglycemic in the fasting state. The underlying type 2 diabetes can only be documented, if at all, by the oral glucose tolerance test and/or the finding of diabetic complications.

The best data on the natural history of diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes are provided by the UKPDS study:[40] in a cohort of 5097 subjects, the annual rate of progression from normo-to-microalbuminuria was 2%, from micro-to-macroalbuminuria was 2.8% and from macroalbuminuria to elevation of serum creatinine was 2.3%.The annual death rate was 0.7% in normo-, 2.0% in micro- and 3.5% in macroalbuminuric patients and was 12.1% in those with elevated serum creatinine.

Albuminuria/proteinuria: Predictor and treatment target

In the past, it was thought that albuminuria was always the consequence of diabetic nephropathy. It is relevant, however, that albuminuria may not only be the consequence of diabetes but may also predict future diabetes as found in the DESIR study.[41] There is currently a debate at what point in the natural history from prediabetes to overt diabetes diabetic nephropathy actually starts. It is of interest that sporadic patients with diffuse diabetic glomerulosclerosis[42] and even nodular diabetic glomerulosclerosis[43] have been encountered in patients with pathological glucose tolerance who developed diabetes only much later; it is difficult to decide whether these patients had diabetes in the past, lost weight and therefore lost hyperglycemia or whether diabetic nephropathy may develop at levels of glycemia that are lower than the current definition of diabetes type 2. In this context, it is also relevant that the onset of type 2 diabetes is predicted by albuminuria.[44]

Following the first studies of Mogensen, Parving and Viberti on albuminuria in diabetes, it has been consistently documented that in diabetic patients who do not have overt proteinuria (>300 mg/day), the presence of albumin in the urine is a powerful predictor of cardiovascular events, of progressive loss of GFR and of mortality.[4546] In the early days, the sensitivity of urine albumin tests had been limited. Patients who did not have overt proteinuria, but who had albumin concentrations beyond the then-available detection threshold for albumin (approximately 30 mg/day), were given the diagnosis of “microalbuminuria.” As time went by, it has been appreciated that even urine albumin concentrations <30 mg/day predict renal and cardiovascular outcomes so that many investigators postulate to abandon the concept of “microalbuminuria” and to treat urinary albumin concentrations as a continuous variable as, for instance, serum cholesterol.[47]

The predictive value of albumiuria is increased if eGFR is monitored concomitantly,[45] because both parameters independently predict progression of nephropathy (and of cardiovascular events). It is of interest that albuminuria predicts cardiovascular events even in the absence of diabetes.[4849] Proteinuria is correlated to the yearly loss of GFR in type 2 diabetes.[50] The reason why in diabetes albuminuria is so predictive of nephropathy may be explained by the fact that glycated albumin is more nephrotoxic than nonglycated albumin, as was found in animal experiments.[51] According to the AUSDIAB study in the early stages of type 2 diabetes, albuminuria is related to both HbA1c and systolic blood pressure[52] – potential targets of intervention, because, in the UKPDS study, the effect of blood glucose and of blood pressure reduction were additive.[53]

On the horizon are markers beyond urinary albumin such as neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipokalin (NGAL).[54] exosomes and microvescicles, i.e. cell membrane-bounded cell wall particles, the content of which is specific for the respective kidney disease[55] or proteomics (SELDI/TOF).[56] Numerous further predictors have been identified with more or less practical relevance, e.g. plasma uric acid concentration as a predictor of macroalbuminuria.[57]

The question has been raised whether albuminuria/[58] proteinuria is a legitimate treatment target. The IDNT[59] study clearly showed that patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD in whom the angiotensin II receptor blocker Irbesartan reduced albuminuria had less renal events than patients without such reduction; obviously, albuminuria is a valid treatment target[60] – not to the least because reduction of microalbuminuria[61] and reduction of proteinuria in more advanced stages of diabetic nephropathy is associated with less cardiovascular events.[62]

In type 2 diabetes, the main targets for intervention are:

-

albuminuria/proteinuria

-

glycemia

-

blood pressure and

-

rennin–angiotensin system

Treatment targets: HbA1c

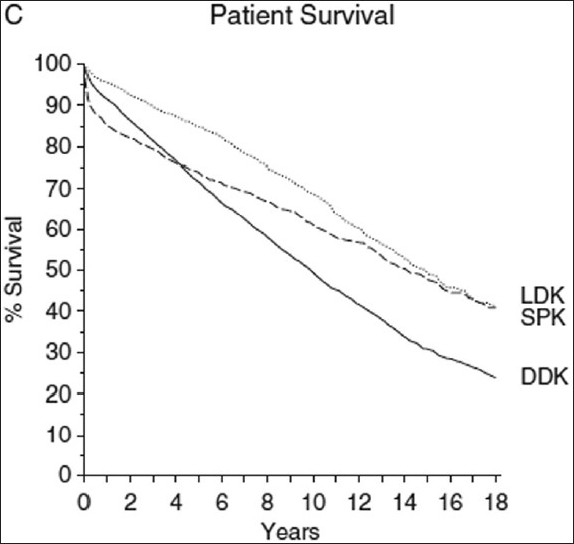

In the ARIC study, HbA1c was a powerful predictor of diabetic nephropathy.[63] It is specifically glycemia in the first 10 years of type 2 diabetes that determines the long-term cardiovascular and renal outcome as first found by Pirart[58] and confirmed by numerous other studies. The UKPDS study showed that even a limited period of stringent glycemic control early on lowered the risk of microvascular disease after 10 years by almost 20%.[64] The explanation for this “glycemic memory” or “legacy” effect is mainly the epigenetic modification of genomic DNA,[65] which causes permanent modification of transcription. “Glycemic memory” and its time course is illustrated by an interesting observation in type 1 diabetic patients. Morath[6667] studied the long-term survival of type 1 diabetic patients who had either received simultaneous pancreas kidney transplantation, live donor kidney transplantation or cadaver kidney transplantation. It took years before patients with simultaneous pancreas kidney transplantation (and subsequent normoglycemia) showed a survival advantage as compared with live donor kidney transplantation, a result of less cardiovascular events [Figure 1].

- Survival of type 1 diabetic patients receiving alive donor kidney (LDK), simultaneous pancreas kidney transplants (SPK) or dead donor kidney (DDK) [Morath et al., JASN (2008) 19:1557]

With respect to glycemic control, there has recently been much controversy on the optimal target HbA1c value. In the Advance study,[68] intensified treatment with Gliclazide on top of routine diabetic medication achieved HbA1c values of 6.5% vs. 7.3% in the control group. This resulted in a 21% reduction of the renal endpoints and a 31% reduction of new macroalbuminuria in the group with intensified glycemic control. Specifically, less microvascular events occurred.[69] In contrast, recent studies in elderly patients with a long duration of diabetes and frequent secondary complications showed that HbA1c was aggressively lowered; with the exception of microalbuminuria, either no significant reduction of microvascular events, of major cardiovascular events or of death were noted[70] or even increased mortality was seen.[71]

It appears sensible to optimize HbA1c aggressively in the early stages of type 2 diabetes without advanced target organ damage and to be more circumspect and tolerate higher HbA1c values in patients with a long duration of diabetes and advanced secondary complications. The evidence of benefit from HbA1c <7 is better for microvascular endpoints than for macrovascular endpoints.[72]

With respect to achieving lower HbA1c values, the main available strategies are either to provide insulin or to sensitize the response to insulin. This has implications for the evolution of diabetic nephropathy. The administration of insulin is associated with weight gain and a greater risk of weight gain and of hypoglycemia. The risk of hypoglycemia is considerably greater in patients with advanced reduction of GFR, because of increased insulin half-life on the one hand and less renal production of glucose to counteract hypoglycemia on the other hand.

To limit the discussion to type 2 diabetic patients with kidney disease, two relatively novel forms of glycemic control are of specific interest, i.e. glitazones and SGLT2 inhibitors.

Glitazones lower glycemia by sensitizing tissues for the action of insulin, but they also have a number of desirable effects beyond glycemic control. Specifically, as compared with metformin in the PROACTIVE study, pioglitazone caused a significantly greater reduction of the albumin-creatinine ratio in the urine.[73] Glitazones also cause a modest reduction of blood pressure and facilitate control of hypertension,[74] and at least Pioglitazone decreased the cardiovascular endpoints in type 2 diabetic patients in whom renal function was reduced,[62] whereas the competitor Rosiglitazone apparently tended to increase cardiovascular events.[75] An important problem requiring mention is the side-effects of sodium and fluid retention as well as triggering congestive heart failure, which require attention to sodium intake, diuretic treatment and exclusion of the underlying cardiac problems.[76]

Glitazones apparently have beneficial effects on the kidney even in nondiabetic kidney disease, as shown in animal models.[77] Recently, Pioglitazone has been shown to even reduce glomerular changes in senescent rats.[78]

A second intervention of specific interest to the nephrologists is the development of inhibitors of sodium–glucose cotransport in the proximal tubule. In the kidney, Na+–glucose cotransport is mediated by the SGLT2 transporter in the S1 segment of the proximal tubule. Mutations of the transporter cause hereditary glucosuria without any systemic side-effects. Similarly, novel specific inhibitors of the Na+–glucose cotransport[79] increase glucose loss in the urine (which is desirable), reduce fasting plasma glucose, cause a modest increase of natriuresis and a modest decrease of blood pressure as well as a moderate weight loss. The Na+–glucose cotransport inhibitor Dapagliflozin was effective in controlling HbA1c in type 2 diabetic patients with inadequate glycemic control on metformin.[80]

Target blood pressure

It is important that elevation of blood pressure in type 2 diabetes is not only the consequence of renal damage. Hsu[81] showed that blood pressure values even within the normotensive range predicted future ESRD in nondiabetic and, even more so, in diabetic individuals, and the risk of developing type 2 diabetes is 2.5-fold higher in hypertensive individuals.[82] It is also important that not all antihypertensives are equal with respect to the risk of developing type 2 diabetes: the incidence of de novo diabetes is significantly lower with blockers of the rennin-angiotensin system,[83] presumably because β-cells are prone to ANGII-induced injury.[84]

Currently, there are ongoing discussions concerning the optimal technique of blood pressure measurement as well as the appropriate target blood pressure.

The study of Kamoi[85] showed that compared with clinic blood pressure measurement, self-measurement of blood pressure by the patient in the morning predicted much better diabetic complications, i.e. nephropathy, retinopathy and coronary heart disease. Therefore, patients should be educated to measure their own blood pressure. It is of interest that in type 1 diabetes, high night-time blood pressure preceded the onset of microalbuminuria[86] and in type 2 diabetes, nocturnal blood pressure elevation also predicted the progression of albuminuria;[87] these observations illustrate the potential usefulness of 24-h blood pressure measurements.

There has also been some recent discussion on whether lowering the systolic blood pressure by antihypertensive medication actually provided any benefit in type 2 diabetes. A metaanalysis of Mancia[88] showed that in almost all studies, benefit with respect to endpoints was significantly greater in patients randomized to more-intensive blood pressure lowering compared with less-intensive blood pressure lowering. In the ADVANCE study,[89] further reduction of blood pressure reduced renal events when the blood pressure was lowered in individuals with baseline systolic blood pressure <120 mmHg. These patients had limited target organ damage.

Aggressive blood pressure lowering may no longer be safe in more advanced stages with higher cardiovascular and renal damage. In the IDNT study, Berl[90] found that the lower the diastolic blood pressure, the higher the risk of myocardial infarction [Figure 2]; in patients with coronary heart disease or other cardiac disease, coronary perfusion (which occurs only during diastole) may be compromised if the diastolic blood pressure is low. In the ONTARGET study,[91] in patients at high cardiovascular risk, the major primary endpoints were more frequent if the baseline systolic blood pressure was <130 mmHg.

- Relative risk of myocardial infarction as a function of diastolic blood pressure in type 2 diabetic patients with impaired renal function (IDNT study) [Berl et al., JASN (2005) 16:2170]

Blockade of the renin–angiotensin system

In diabetes, the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) is activated. Blockade of the RAS by ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers reduces proteinuria. A metaanalysis by Jafar (73) showed that RAS blockade did not only lower proteinuria but also caused significant reduction of progression at least in patients with baseline urinary protein excretion >1 g/day. The same has been shown for angiotensin receptor blockers.[92–94] Thus, RAS blockade is certainly indicated in proteinuric type 2 diabetic patients. It would be wrong, however, to assume that RAS blockade per se is sufficient. As shown in Figure 3,[95] the effect of lowering blood pressure in the Amlodipine arm of the study was greater than the effect of RAS blockade in the Irbesartan arm. Apart from insufficient lowering of 24-h blood pressure (including nighttime blood pressure), further causes of insufficient reduction of proteinuria are excessive NaCl intake, insufficient diuretic dose (in proteinuric patients, protein-bound diuretics fail to block Na+ reabsorption) and aldosterone “escape”.

- Average achieved systolic blood pressure and renal endpoints (a) and all-cause mortality (b) in type 2 diabetic patients with impaired renal function (IDNT study) [Pohl et al., JASN (2005) 16:3027]

Unfortunately, monotherapy is usually insufficient to achieve target blood pressure values. This raises the issue, which additional antihypertensive agents should be combined with RAS blockade. The ACCOMPLISH trial showed that benazepril plus hydrochlorothiazide was less effective in reducing renal events than benazepril plus amlodipine.[96] Nevertheless, reduction of dietary sodium intake[97] and diuretics is usually required in diabetic patients with impaired renal function.

What is the evidence that in advanced diabetic nephropathy, progression to end-stage kidney disease can be influenced.

A frequent problem in diabetic nephropathy is inadequate reduction of proteinuria or initial successful lowering with a secondary increase in proteinuria, the so-called “escape” phenomenon. In the patient with escape, the following approaches are available to the physician [Table 1].

Salt restriction causes upregulation of the RAS and increases the response to RAS blockade. Patients must be educated to reduce salt intake, and this should be monitored by measuring the 24-h urine sodium excretion.[97] The doses of diuretics should be adapted to the magnitude of proteinuria (diuretics are protein-bound and act from within the tubular lumen); the presence of proteinuria in the effective free (nonprotein-bound) concentration is reduced.

It has become apparent that the doses licensed for blood pressure reduction may not be the optimal dose to reduce proteinuria and inhibit progression. Therefore, dose escalation of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers can be advised. There is no superiority of combining ACE inhibitors with angiotensin receptor blockers at least in microalbuminuric type 2 diabetic patients.[98]

The escape phenomenon is linked to an increase in aldosterone concentrations. A number of studies[99–102] showed that Spironolactone or Eplerenone, i.e. mineralocorticoid receptor blockers, reduce the risk of escape and can achieve reversal of escape.

An investigational drug is currently the renin inhibitor Aliskiren, which has been shown to reduce proteinuria,[103] and a current study examines whether progressive loss of GFR can be beneficially affected.

In animal experiments, endothelin receptor blockers were highly effective in diabetic nephropathy. We had shown that relatively low doses of the endothelin A receptor blocker, Avosentan, reduce albuminuria in early stages of type 2 diabetes with nephropathy.[104] Unfortunately, patients with more advanced diabetic nephropathy and treated with relatively high doses with Avosentan had major side-effects mostly related to sodium retention, and fluid overload was noted.[105] The novel, more ETA receptor-selective blocker Atrasentan appears to be promising in this indication (Kohan, JASN in press).

Active vitamin D has been shown to reduce glomerulosclerosis and proteinuria in renal damage models.[106] De Zeeuw recently showed that the vitamin D receptor agonist paricalcitol reduced albuminuria in type 2 diabetes without causing hypercalcemia at the dose examined.[107]

In preclinical trials, further approaches such as renin receptor inhibitors, AT2 receptor agonists and chymase inhibitors are under examination.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Diabetes mellitus in the texts of old Hindu medicine (Charaka, Susruta, Vagbhata) Am J Gastroenterol. 1957;27:76-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- The metabolic syndrome and associated risk factors in an urban industrial male population in South India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2010;58:363-6-371.

- [Google Scholar]

- Time trends in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus: Ten year analysis from southern India (1994-2004) on 19,072 subjects with diabetes. J Assoc Physicians India. 2010;58:290-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes: Indian scenario. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:217-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its influence on microvascular complications in the Indian population with Type 2 diabetes mellitus.Sankara Nethralaya Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology And Molecular Genetic Study (SN-DREAMS, report 14) Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2010;2:67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glucose intolerance (diabetes and IGT) in a selected South Indian population with special reference to family history, obesity and lifestyle factors--the Chennai Urban Population Study (CUPS 14) J Assoc Physicians India. 2003;51:771-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alterations in HbA(1c) with advancing age in subjects with normal glucose tolerance: Chandigarh Urban Diabetes Study Group. Diabet Med 2011 [In Press]

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of overweight and obesity in Indian adolescent school going children: Its relationship with socioeconomic status and associated lifestyle factors. J Assoc Physicians India. 2010;58:151-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES)--study design and methodology (urban component)(CURES-I) J Assoc Physicians India. 2003;51:863-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes prevalence and its risk factors in rural area of Tamil Nadu. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:396-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for microvascular complications of diabetes among South Indian subjects with type 2 diabetes--the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES) Eye Study-5. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12:755-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chronic kidney disease in India: Challenges and solutions. Nephron Clin Pract. 2009;111:c197-203.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current status of end-stage renal disease care in South Asia. Ethn Dis. 2009;19:S1-27-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- The incidence of end-stage renal disease in India: A population-based study. Kidney Int. 2006;70:2131-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spectrum of renal disorders in a tertiary care hospital in Haryana. J Assoc Physicians India. 2007;55:198-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical spectrum of chronic renal failure in the elderly: A hospital based study from eastern India. Int Urol Nephrol. 2006;38:821-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and risk factors of diabetic nephropathy in an urban South Indian population: The Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES 45) Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2019-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence and clinical characteristics of renal insufficiency in diabetic patients. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2001;126:1322-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non diabetic renal disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nephrology (Carlton). 2006;11:533-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening for type 2 diabetes in a multiethnic setting using known risk factors to identify those at high risk: A cross-sectional study. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2010;6:837-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- High incidence of end-stage renal disease in Indo-Asians in the UK. QJM. 1995;88:191-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Differences in progression of CKD and mortality amongst Caucasian, Oriental Asian and South Asian CKD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:3663-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lack of awareness of kidney complications despite familiarity with diabetes: A multi-ethnic qualitative study. J Ren Care. 2011;37:2-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Raising the priority of preventing chronic diseases: A political process. Lancet. 2010;376:1689-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term effects of a randomised trial of a 6-year lifestyle intervention in impaired glucose tolerance on diabetes-related microvascular complications: The China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcome Study. Diabetologia. 2011;54:300-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- End-stage renal failure in type 2 diabetes: A medical catastrophe of worldwide dimensions. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;34:795-808.

- [Google Scholar]

- Level of renal function in patients starting dialysis: An ERA-EDTA Registry study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:3315-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increasing incidence of proteinuria and declining incidence of end-stage renal disease in diabetic Pima Indians. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1840-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nonalbuminuric renal insufficiency in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:195-200.

- [Google Scholar]

- UKPDS Study Group. Risk factors for renal dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study 74. Diabetes. 2006;55:1832-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal insufficiency in the absence of albuminuria and retinopathy among adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2003;289:3273-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cerebral microvascular disease predicts renal failure in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:520-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chronic dialysis and death among survivors of acute kidney injury requiring dialysis. JAMA. 2009;302:1179-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development and progression of nephropathy in type 2 diabetes: The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS 64) Kidney Int. 2003;63:225-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urinary albumin excretion is a risk factor for diabetes mellitus in men, independently of initial metabolic profile and development of insulin resistance. The DESIR Study. J Hypertens. 2008;26:2198-206.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diffuse diabetic glomerulosclerosis in a patient with impaired glucose tolerance: Report on a patient who later develops diabetes mellitus. Neth J Med. 2002;60:260-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nodular glomerulosclerosis in a patient with metabolic syndrome without diabetes. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2008;4:639-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urinary albumin excretion and its relation with C-reactive protein and the metabolic syndrome in the prediction of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2525-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Albuminuria and kidney function independently predict cardiovascular and renal outcomes in diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1813-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of mortality of patients newly diagnosed with clinical type 2 diabetes: A 5-year follow up study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2010;10:14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urinary albumin excretion predicts cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality in general population. Circulation. 2002;106:1777-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of albuminuria on cardiovascular risk in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2007;116:2687-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Remission to normoalbuminuria during multifactorial treatment preserves kidney function in patients with type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;9:2784-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intraperitoneal protein injection in the axolotl: The amphibian kidney as a novel model to study tubulointerstitial activation. Kidney Int. 2002;62:51-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Albuminuria is evident in the early stages of diabetes onset: Results from the Australian Diabetes, Obesity, and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab) Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:792-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Additive effects of glycaemia and blood pressure exposure on risk of complications in type 2 diabetes: A prospective observational study (UKPDS 75) Diabetologia. 2006;49:1761-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changes of serum and urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in type-2 diabetic patients with nephropathy: One year observational follow-up study. Endocrine. 2009;36:45-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nucleic acids within urinary exosomes/microvesicles are potential biomarkers for renal disease. Kidney Int. 2010;78:191-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serum uric acid as a predictor for development of diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes: An inception cohort study. Diabetes. 2009;58:1668-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes mellitus and its degenerative complications: A prospective study of 4,400 patients observed between 1947 and 1973 (3rd and last part) (author's transl) Diabete Metab. 1977;3:245-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proteinuria reduction and progression to renal failure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and overt nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:281-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Albuminuria is a target for renoprotective therapy independent from blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy: Post hoc analysis from the Reduction of Endpoints in NIDDM with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan (RENAAL) trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1540-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reduction in microalbuminuria as an integrated indicator for renal and cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007;56:1727-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of pioglitazone on cardiovascular outcome in diabetes and chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:182-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Poor glycemic control in diabetes and the risk of incident chronic kidney disease even in the absence of albuminuria and retinopathy: Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2440-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1577-89.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epigenetics: Mechanisms and implications for diabetic complications. Circ Res. 2010;107:1403-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic control improves long-term renal allograft and patient survival in type 1 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1557-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transplantation of the type 1 diabetic patient: The long-term benefit of a functioning pancreas allograft. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:549-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Blood pressure and glucose control in subjects with diabetes: New analyses from ADVANCE. J Hypertens Suppl. 2009;27:S3-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2560-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:129-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2545-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intensive glycemic control and the prevention of cardiovascular events: Implications of the ACCORD, ADVANCE, and VA diabetes trials: A position statement of the American Diabetes Association and a scientific statement of the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:187-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microalbuminuria as a marker of cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Cardiol. 2006;107:147-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ambulatory blood pressure reduction after rosiglitazone reatment in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension correlates with insulin sensitivity increase. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1769-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular risk and thiazolidinediones--what do meta-analyses really tell us? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12:1023-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thiazolidinedione use, fluid retention, and congestive heart failure: A consensus statement from the American Heart Association and American Diabetes Association. October 7, 2003. Circulation. 2003;108:2941-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The PPARgamma agonist pioglitazone ameliorates aging-related progressive renal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2380-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sodium-glucose cotransport inhibition with dapagliflozin in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:650-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of dapagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes who have inadequate glycaemic control with metformin: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:2223-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Elevated blood pressure and risk of end-stage renal disease in subjects without baseline kidney disease. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:923-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypertension and antihypertensive therapy as risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus.Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:905-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Why blockade of the renin-angiotensin system reduces the incidence of new-onset diabetes. J Hypertens. 2005;23:463-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improved islet morphology after blockade of the renin- angiotensin system in the ZDF rat. Diabetes. 2004;53:989-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Usefulness of home blood pressure measurement in the morning in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2218-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increase in nocturnal blood pressure and progression to microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:797-805.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nocturnal blood pressure elevation predicts progression of albuminuria in elderly people with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10:12-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reappraisal of European guidelines on hypertension management: A European Society of Hypertension Task Force document. J Hypertens. 2009;27:2121-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lowering blood pressure reduces renal events in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:883-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of achieved blood pressure on cardiovascular outcomes in the Irbesartan Diabetic Nephropathy Trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2170-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prognostic value of blood pressure in patients with high vascular risk in the Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial study. J Hypertens. 2009;27:1360-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Angiotensin-receptor blockade versus converting-enzyme inhibition in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1952-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:851-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:861-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Independent and additive impact of blood pressure control and angiotensin II receptor blockade on renal outcomes in the irbesartan diabetic nephropathy trial: Clinical implications and limitations. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3027-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal outcomes with different fixed-dose combination therapies in patients with hypertension at high risk for cardiovascular events (ACCOMPLISH): A prespecified secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1173-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benefits of dietary sodium restriction in the management of chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens,. 2009;18:531-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of microalbuminuria in hypertensive subjects with elevated cardiovascular risk: Results of the IMPROVE trial. Kidney Int. 2007;72:879-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness of aldosterone blockade in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Hypertension. 2003;41:64-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aldosterone escape during blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in diabetic nephropathy is associated with enhanced decline in glomerular filtration rate. Diabetologia. 2004;47:1936-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system triple blockade on non-diabetic renal disease: Addition of an aldosterone blocker, spironolactone, to combination treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin II receptor blocker. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:59-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Addition of angiotensin receptor blockade or mineralocorticoid antagonism to maximal angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2641-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- AVOID Study Investigators.Aliskiren combined with losartan in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2433-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Avosentan reduces albumin excretion in diabetics with macroalbuminuria. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:655-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of 1,25 (OH)2 vitamin D3 on glomerulosclerosis in subtotally nephrectomized rats. Kidney Int. 1998;53:1696-705.

- [Google Scholar]

- Selective vitamin D receptor activation with paricalcitol for reduction of albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes (VITAL study): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. ;376:1543-51.

- [Google Scholar]