Translate this page into:

Spectrum of lymphoproliferative disorders following renal transplantation in North India

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) is a well-recognized, but uncommon complication of organ transplantation. This study was a retrospective analysis of 2000 patients who underwent renal transplantation over a period of 30 years (1980-2010). Forty malignancies were diagnosed in 36 patients. Of these, 29 patients (1.45%) had PTLD (7 females, 22 males) accounting for 72.5% of all malignancies after transplantation. Twenty-two (75.8%) developed non-Hodgkin lymphoma and seven patients (24.2%) had myeloma. Diagnosis was made by biopsy of the involved organ in 21 patients (72.4%) and aspiration cytology in five patients (17.2%). In three patients, the diagnosis was made only at autopsy. Mean age at the time of diagnosis of PTLD was 41.9 years (range 21-69 years). Time interval from transplantation to the diagnosis of PTLD ranged from 3 months to 144 months with a median of 48 months. Only five patients (17.2%) developed PTLD within a year of transplantation. Twelve patients developed PTLD 1-5 years and 12 patients 5-10 years after transplantation. Organ involvement was extra nodal in 18 patients (82%). Thirteen (59%) patients had disseminated disease and nine (41%) had localized involvement of a single organ (brain-3, liver-1, allograft-1, perigraft node-1, retroperitoneal lymph nodes-3). Infiltration of the graft was noted in two patients. Patients with myeloma presented with backache, pathological fracture, unexplained anemia or graft dysfunction. PTLD was of B cell origin in 20 cases (70%). CD 20 staining was performed in 10 recent cases, of which 8 stained positive. Of the 26 patients diagnosed during life, 20 (69%) died within 1 year of diagnosis despite therapy. In conclusion, PTLD is encountered late after renal transplantation in the majority of our patients and is associated with a dismal outcome. The late onset in the majority of patients suggests that it is unlikely to be Epstein Barr virus related.

Keywords

Epstein Barr virus

extra nodal

immunosuppression

malignancy

Introduction

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) is an unusual malignancy that is characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of lymphocytes in the setting of post-transplant immunosuppression. The reported incidence in renal transplant recipients ranges from 1% to 2.5%.[123] The majority of PTLD represent proliferation of transformed B cells following infection with Epstein Barr virus (EBV).[4] Histologically, these tumors may appear polymorphic (containing B cells at more than one stage of development) or monomorphic (usually large B cells).[5] Risk factors for the development of PTLD include post-transplant primary EBV infection, the type and intensity of immunosuppression, cytomegalovirus disease, and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.[6] Despite therapy, the mortality remains high (up to 70%) in patients with PTLD.[7] There is a paucity of data on the incidence and characteristics of PTLD from India. We undertook a retrospective analysis of the clinical features, pathology, and outcome of 29 cases of PTLD diagnosed at our center.

Materials and Methods

This study was a retrospective analysis of the medical records of 2000 patients who underwent renal transplantation from living related donors over a period of 30 years (1980-2010) at our center. Patients transplanted prior to 1992 received only azathioprine (AZA) and prednisolone. Those transplanted between 1992 and 2003 received cyclosporine (CsA), AZA and steroids while from 2004 onward, most patients received tacrolimus (Tac) and steroids with either AZA or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). Tissue biopsy, fine needle aspiration, and fluid cytology were used for diagnosis. Tumors were classified as monomorphic or polymorphic PTLD and plasma cell myeloma (bone marrow plasma cells >10%) based on morphological appearance. Immunophenotyping for B cell and T cell markers was carried out in all cases. Immunostaining for CD 20 was performed for 10 patients seen in the last 12 years.

Results

Forty malignancies were diagnosed in 36 patients after transplantation. Of these 29 patients, (1.45%) had PTLD (7 females, 22 males) accounting for 72.5% of all malignancies after transplantation. A total of 22 patients had non-Hodgkin lymphomas and seven patients had plasma cell myeloma. All 29 patients had received their first graft. Mean age at the time of diagnosis of PTLD was 41.9 years (range 21-69 years). Time interval from transplantation to the diagnosis of PTLD ranged from 3 months to 144 months with a median of 48 months. Only five patients (17.2%) developed PTLD within a year of transplantation. Twelve patients developed PTLD 1-5 years and 12 patients 5-10 years after transplantation. Initial immunosuppressive therapy consisted of CsA, Aza, and prednisolone in 23 patients, dual therapy with AZA and prednisolone in two patients, Tac, Aza, and prednisolone in two and Tac, MMF, and prednisolone in two patients. Two patients received induction with Basiliximab and none with ATG or OKT-3.

Clinical presentation

The clinical presentation of PTLD was highly variable, a reflection of the range of organs involved by the tumor. Table 1 summarizes the clinical presentation and organ involvement by PTLD. The predominant presenting symptoms included fever (27.2%), abdominal pain and/or mass (27.7%), headache (13.6%), and backache (4.5%). Organ involvement was primarily extranodal in 18 patients (82%). Thirteen (59%) patients had disseminated disease and nine (36.4%) had localized involvement of a single organ (brain-3, liver-1, allograft-1, perigraft node-1, retroperitoneal lymph nodes-3). In patients with disseminated disease, the gastrointestinal tract, mesentery, liver, bone marrow, and lymph nodes were the organs commonly involved. Graft involvement in the form of direct infiltration was seen in two patients; one was diagnosed on graft biopsy done for evaluation of graft dysfunction while the other was detected at autopsy. One patient presented clinically with a perigraft mass.

Clinical presentation in patients with myeloma included backache (28.5%), severe anemia (28.5%), pathological fracture (57.1%), and graft dysfunction due to light chain deposition disease (LCDD) (14.3%) [Table 1].

A second malignancy developed subsequently in two patients; one patient had well- differentiated adenocarcinoma of the cecum and ascending colon and one patient had carcinoma in situ of the cervix. Seventeen patients were tested for anti HCV antibody of whom only one was positive and none had HBV infection. Eight patients were tested for Immunoglobin G antibodies to EBV and only one had detectable levels.

Tumor pathology

Diagnosis was made by biopsy of the involved organ in 23 patients (79.3%) and aspiration cytology in three patients (10.3%). In three patients, the diagnosis was made only at autopsy. Lymphoma was of B cell origin in 20 cases (91%). In 18 patients (81.8%), B cell PTLD was composed of uniform appearing lymphoid cells at a predominantly single stage of differentiation (monomorphic PTLD), an appearance resembling non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Two patients were diagnosed as having T cell lymphoma and seven patients had plasma cell myeloma. CD 20 staining was performed in 10 patients of whom 8 stained positive.

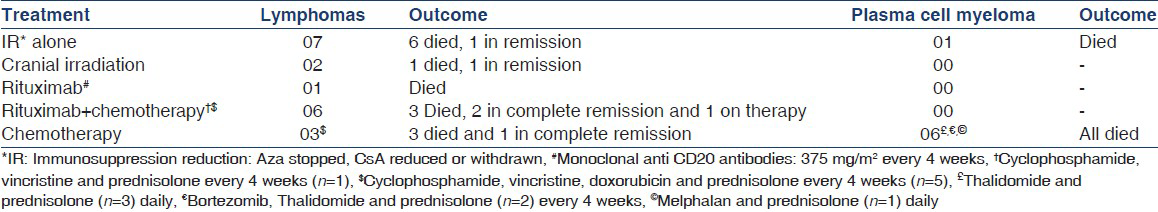

Treatment and outcome

The response to various treatment modalities and the clinical outcomes are described in Table 2. In all patients, immunosuppression was reduced; AZA or MMF was discontinued and CsA/Tac was either withdrawn or reduced. Five patients seen in the last 7 years were started on sirolimus in place of CsA/Tac after the diagnosis of PTLD. None of the patients had acute rejection episodes after reduction in immunosuppression. Of the 19 lymphoma patients diagnosed during life, 14 (73.68%) died within 1 year of diagnosis. Of those with plasma cell myeloma, all died within 1 year of diagnosis. Of the five patients presently on follow up, one patient with isolated bone marrow involvement has been disease free for 2 years following immunosuppression reduction alone, a second patient is in remission for >5 years following cranial irradiation for isolated central nervous system (CNS) disease, a third patient has complete remission for >3 year following Rituximab and chemotherapy (CHOP), the fourth patient received CHOP and has shown complete resolution of the lesions 12 months after the diagnosis and the fifth patient who received Rituximab plus CHOP developed a CNS relapse after being in remission for 2 years.

Discussion

This is the largest number of cases of PTLD to be reported from a single center in India. The incidence of PTLD in our study was 1.45%. In a study from another referral center of the region nine cases of PTLD were reported among 1700 transplant patients (incidence of 0.5%).[8] Analysis of the ANZDATA registry and USRDS revealed PTLD incidence rates of 1.4% in both.[23] While the incidence of PTLD in our patients is similar to that reported from elsewhere, PTLD is by far the most common malignancy accounting for 72.5% of all tumors in our patients. In contrast, data from the Cincinnati Tumor Transplant Registry revealed that PTLD accounted for 21% of all cancers post-transplant and at the Oxford transplant center only 16% of all post-transplant malignancies were due to PTLD.[910] The high proportion of PTLD among all cancers observed in this study is partly a result of the rarity of skin cancers in our patient population.

In this study, PTLD developed after a median interval of 48 months following transplantation. Twenty-five patients (86%) developed PTLD more than 1 year after transplantation (late PTLD). This contrasts with the findings of the Collaborative transplant study in which the incidence of PTLD was highest in the 1st year following transplantation and fell by about 80% thereafter.[1] An analysis of data from the USRDS revealed that 58% of 344 patients developed PTLD in the 1st year of transplantation.[3] In the Oxford study however, only 5 of the 27 patients (18.3%) developed lymphoma in the 1st year after transplantation.[10] Late PTLDs differ significantly from early PTLDs in that they are less influenced by the degree of immunosuppression, generally lack EBV genome in their tumor cells and are more likely to be monomorphic and monoclonal.[11] There are at least two reports of PTLD from the Indian subcontinent. Madhivanan et al.,[12] and Jain et al.,[8] had reported late onset disease in 79% and 100% of PTLD patients respectively and the median period of development of PTLD was 7 years (range 4-11 years) in the series reported from Lucknow.[8]

In situ hybridization for EB encoded RNA (EBER), southern blotting for detection of EBV DNA and immunohistochemistry to detect viral latent membrane protein-1 are the definitive methods for detecting EBV infection. There was inadequate data on EBV infection in patients diagnosed with PTLD in this study. However, in view of its late onset, PTLD in most of our patients is unlikely to have been EBV related.[13] However, few studies have reported EBV positivity in as many as 38-44% of late onset PTLD.[1314]

Monomorphic PTLD accounted for 18 out of the 20 cases of B cell and both T cell PTLD cases in our study. PTLD commonly involves extranodal sites at the time of diagnosis. In our study, 18 patients (82%) had extranodal presentation. The disease was disseminated at the time of diagnosis in 13 patients (59%). Thus, the diagnostic evaluation of PTLD must include extensive imaging studies and bone marrow biopsy to identify the site and extent of involvement. In 18% of lymphomas, the allograft and/or the nodes around the graft are involved.[9] In our study, two patients had infiltration of the graft of whom one presented with graft dysfunction. PTLD remains an significant cause for late onset acute graft dysfunction and it is therefore important to differentiate it from acute rejection. One patient with myeloma also presented with graft dysfunction and had biopsy proven LCDD in the allograft. CNS lymphoma is usually a part of disseminated lymphoma in the general population, but is usually restricted to the CNS in transplant recipients.[9]

The ideal treatment for PTLD is still controversial. Reduction of immunosuppression is recommended in all patients and may be the only treatment required in some cases. CHOP can be offered to patients with frankly malignant tumors (monoclonal, monomorphic), but achieves only short remissions. Three patients in our study who were given CHOP alone died within 10 months after therapy. Rituximab, a chimeric anti-CD20 antibody has been approved for the treatment of B cell follicular non-Hodgkin lymphomas. One report of a multicenter experience with the use of Rituximab in the treatment of 32 cases of CD 20 +ve PTLD showed encouraging response rates of 76% and 47% for early and late PTLD respectively.[15] Rituximab can be combined with CHOP. We treated five patients with CD 20 +ve PTLD with a combination of Rituximab and CHOP of whom only two patients had a complete remission. Five of our patients were started on sirolimus in place of CsA after the diagnosis of PTLD. In vitro studies suggest that sirolimus may have anti-cancer activity.[16] Observational studies in renal transplantation have shown a reduced incidence of malignancy in patients receiving sirolimus compared to those on calcineurin inhibitors.[17]

In a retrospective analysis of 7040 renal transplant recipients, 78 patients developed PTLD of which only five had plasmacytoma.[18] Multiple myeloma in transplant recipients is rare probably because myeloma is a disease of elderly and renal transplant recipients in India are relatively usually young. However, compared to the general population, renal transplant recipients are at 4.4-fold higher risk of developing myeloma.[19] Post-transplant myeloma is associated with older age, transplant from deceased donors, HCV and EBV infection and use of ATG induction.[20] Most plasma cell myeloma is EBV/HCV associated.[20] The mean age at the time of diagnosis of myeloma in our study was 46.1 years and higher compared to non-myeloma PTLD. The 10-year survival rate of post-transplant myeloma is 26% and lower as compared to non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.[19] However, all patients in our study expired secondary to sepsis and survival in our series in spite of CHOP was lower compared to other reports.[20]

The major limitations of this study include the retrospective nature of the analysis, the lack of information on tissue markers of EBV infection and the heterogeneity of immunosuppression used since these patients were transplanted at different times over three decades.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in kidney and heart transplant recipients. Lancet. 1993;342:1514-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lymphoproliferative disease after renal transplantation in Australia and New Zealand. Transplantation. 2005;80:193-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders after renal transplantation in the United States in era of modern immunosuppression. Transplantation. 2005;80:1233-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) induced polyclonal and monoclonal B-cell lymphoproliferative diseases occurring after renal transplantation. Clinical, pathologic, and virologic findings and implications for therapy. Ann Surg. 1983;198:356-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- The pathology of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders occurring in the setting of cyclosporine A-prednisone immunosuppression. Am J Pathol. 1988;133:173-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pretransplantation assessment of the risk of lymphoproliferative disorder. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1346-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence and consequences of post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorders. J Nephrol. 1997;10:136-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders after live donor renal transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2005;19:668-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lymphoproliferative disorders in Oxford renal transplant recipients. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:439-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lymphomas occurring late after solid-organ transplantation: Influence of treatment on the clinical outcome. Transplantation. 2002;74:1095-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lymphoproliferative disorders in renal transplant recipients: A single-centre experience. Natl Med J India. 2006;19:50-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders not associated with Epstein-Barr virus: A distinct entity? J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2052-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epstein-Barr virus-negative lymphoproliferate disorders in long-term survivors after heart, kidney, and liver transplant. Transplantation. 2000;69:827-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (Rituximab) in post transplant B-lymphoproliferative disorder: A retrospective analysis on 32 patients. Ann Oncol. 2000;11(Suppl 1):113-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The immunosuppressive macrolide RAD inhibits growth of human Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B lymphocytes in vitro and in vivo: A potential approach to prevention and treatment of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4285-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of the type of induction immunosuppression with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder, graft survival, and patient survival after primary kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;76:1289-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lymphoma after solid organ transplantation: Risk, response to therapy, and survival at a transplantation center. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3354-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Twenty and 25 years survival after cadaveric renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:2154-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Myeloma, Hodgkin disease, and lymphoid leukemia after renal transplantation: Characteristics, risk factors and prognosis. Transplantation. 2006;81:888-95.

- [Google Scholar]