Translate this page into:

Changing picture of acute kidney injury in pregnancy: Study of 259 cases over a period of 33 years

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

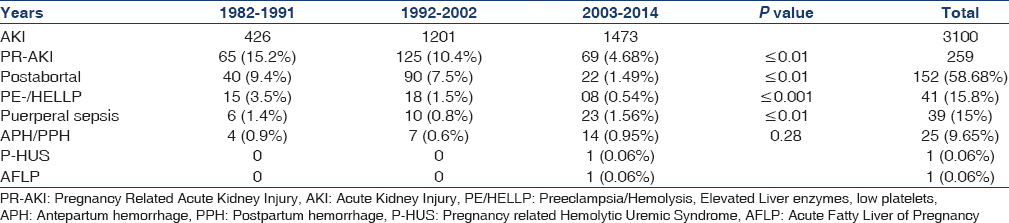

The incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) in pregnancy is declining in developing countries but still remains a major cause of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. The aim of the study was to analyze the changing trends in pregnancy related AKI (PR-AKI) over a period of thirty-three years. Clinical characteristics of PR-AKI with respect to incidence, etiology and fetal and maternal outcomes were compared in three study periods, namely 1982-1991,1992-2002 and 2003-2014. The incidence of PR-AKI decreased to 10.4% in 1992-2002, from 15.2% in 1982-1991, with declining trend continuing in 2003-2014 (4.68%).Postabortal AKI decreased to 1.49% in 2003-2014 from 9.4% in 1982-1991of total AKI cases. The AKI related to puerperal sepsis increased to 1.56% of all AKI cases in 2003-2014 from 1.4% in 1982-1991. Preeclampsia/eclampsia associated AKI decreased from 3.5% of total AKI cases in 1982-1991 to 0.54% in 2003-2014. Pregnancy associated – thrombotic microangiopathy and acute fatty liver of pregnancy were uncommon causes of AKI. Hyperemesis gravidarum associated AKI was not observed in our study. Incidence of renal cortical necrosis (RCN) decreased to 1.4% in 2003-2014 from 17% in 1982-1991.Maternal mortality reduced to 5.79% from initial high value 20% in 1982-1991. The progression of PR-AKI to ESRD decreased to1.4% in 2003-2014 from 6.15% in 1982-1991. The incidence of PR-AKI has decreased over last three decades, mainly due to decrease in incidence of postabortal AKI. Puerperal sepsis and obstetric hemorrhage were the major causes of PR-AKI followed by preeclampsia in late pregnancy. Maternal mortality and incidence and severity of RCN have significantly decreased in PR-AKI. The progression to CKD and ESRD has decreased in women with AKI in pregnancy in recent decade. However, the perinatal mortality did not change throughout study period.

Keywords

Acute kidney injury

CKD

cortical necrosis

preeclampsia

pregnancy

puerperal sepsis

septic abortion

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) in a pregnant woman poses a risk to two lives (mother and fetus). It is largely due to potentially preventable obstetric complications and was a significant cause of maternal mortality and morbidity in the past.[123] With the legalization of abortion and improved antenatal care, the incidence of pregnancy related-AKI (PR-AKI) has declined significantly in most developed countries.[456] The current incidence of PR-AKI in developed countries is estimated to be around 1 in 20,000 pregnancies.[7] Though, the incidence of PR-AKI is declining in developing countries, but it still remains a major contributor to fetal mortality and maternal morbidity with the development of end-stage renal diseases (ESRD).[89] PR-AKI in the third trimester and the postpartum period is associated with high (39%) incidence of fetal/neonatal mortality.[10] Despite a significantly decreased the incidence of AKI in pregnant women, the fetal mortality remains unacceptably high, even in developed countries.

The aim of the present study was to analyze the changing trends in the incidence, etiology, and outcome of PR-AKI over three decades in a tertiary health care center of the eastern part of the country.

Methods

This retrospective, observational study was conducted over a period of 33 years (1982–2014) in the Department of Nephrology, Institute of Medical Sciences, Sir Sunderlal Hospital, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi. The study was divided into three periods, namely 1982–1991, 1992–2002, and 2003–2014. First and second trimesters were considered as early pregnancy; and third trimester and puerperium as late pregnancy for the purpose of this study. A total of 259 patients of PR-AKI referred to our center were included in the study. The age of patients ranged from 18 to 46 years, with a mean of 29.8 years. We used the following criterion for the diagnosis of AKI in pregnancy (any one of the three); (1) serum creatinine >1 mg/dl, (2) oliguria/anuria >12 h duration, and (3) need for dialysis. Intermittent hemodialysis was prescribed using the standard indications of dialysis in patients with dialysis requiring AKI. The demographic, clinical, and laboratory details of all patients with PR-AKI were recorded. The etiology, time of renal failure with respect to gestational age, need of renal replacement therapy (RRT), and outcome in terms of fetal and maternal mortality, and number of women landing into ESRD were noted individually. Specific investigations were carried to exclude uncommon and/or rare cause of AKI. They included ANA, anti-dsDNAab, C3, C4, and antiphospholipid antibody. Platelet count, PT-INR, aPTT, blood smear for schistocyte, lactate dehydrogenase, serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase, and serum glutamic pyruvic transaminases level were estimated. Kidney biopsy was done in patient with anuria and/or oligoanuria of >4 weeks duration and in those with partial recovery of renal function persisting for more than 3 months after the AKI episode. Until 1992, the diagnosis of cortical necrosis was made on the basis of histological finding of ischemic necrosis of all the elements of renal cortex, which could be patchy or diffuse in distribution. After 1992, finding of the hypoattenuated subcapsular rim of cortex on contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan was taken as diagnostic of cortical necrosis.

The incidence, etiology, occurrence of AKI with respect to gestational age, maternal and fetal outcome was compared in the three study periods (1982–1991, 1992–2002, and 2003–2014). Statistical analysis was carried using SPSS 16 (Chicago, SPSS Inc. 2007 Windows, version 16.0). For intergroup comparisons, Chi-square test was used. A P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Over a period of three decades, PR-AKI was responsible for 8.35% (259/3100) of all cases of AKI. The contribution of PR-AKI to total cases of AKI decreased significantly from 15.2% in 1982–1991 to 10.4% in 1992–2002 and further declined to 4.68% in the 2003–2014 periods. Postabortal sepsis accounted for 9.4% of the total AKI cases in 1982–1991, the incidence decreased to 7.5% in 1992–2002; and 1.49% in 2003–2014. We noted that preeclampsia/eclampsia (PE/E) was responsible for 3.5% of total cases of AKI in 1982–1991, which significantly decreased to 0.54% in 2003–2014. AKI due to puerperal sepsis increased from 1.4% in 1982–1991 to 1.56% in 2003–2014. Pregnancy associated- hemolytic uremic syndrome (P-HUS) and acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) were seen in one case each [Table 1]. However, not even a single case of hyperemesis gravidarum associated AKI was seen in last 33 years in early pregnancy. The relative contribution of different obstetrical complications leading to PR-AKI in the three study periods is shown in Figure 1. Puerperal sepsis-associated AKI increased significantly to 26.4% in 2003–2014 from ~ 9% in 1982 to 1991. The fraction of patients with postabortal AKI decreased from 61.5% and 72% in 1982–1991 and 1992–2002, respectively to 31.8% in 2003–2014 (P < 0.01). Preeclampsia/HELLP syndrome associated AKI has decreased significantly from 23% in 1982–1991 to 11.5% in 2003–2014 [Table 2]. The proportion of PR-AKI has increased in the third trimester and puerperium while postabortal AKI decreased significantly, particularly in 2003–2014 [Figure 2].

- Categories of different obstetrical complications leading to PR-AKI in three study periods

- Distribution of cases of PR-AKI with respect to the phase of pregnancy

Percentage of women with PR-AKI needing RRT decreased significantly from 83% and 98.4% in 1982–1991 and 1992–2002, respectively; to 66.6% in 2003–2014 (P < 0.001). Maternal mortality was 20% in 1982-1991 in the acute phase of illness, mainly due to sepsis and uremic complications. However, the maternal mortality decreased significantly (5.79%) in the later periods. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) developed in 10.8% (28/259) of patients following PR-AKI. Seven patients progressed to ESRD. We noted a significant decrease in the number of women with PR-AKI progressing to ESRD in last decade of study [Table 3]. Kidney biopsy in 18 patients with PR-AKI revealed cortical necrosis in 15 (diffuse 8 and patchy 7); class IV lupus nephritis 2; and ESRD histology in one patient. The incidence of renal cortical necrosis (RCN) significantly decreased to 1.44% in 2003–2014 from an initial high incidence of 17% in 1982–1991 (P < 0.001). Of four patients with cortical necrosis in the last 20 years (1992–2014), diffuse and patchy cortical necrosis was observed in 1 and 3 cases, respectively. Thus, both the incidence and severity of RCN have decreased in patients with AKI in pregnancy. However, we noted that perinatal mortality continued to be high (~45%) throughout the three decades. The causes of perinatal mortality included stillbirth, intrauterine death, and premature delivery.

Discussion

Acute kidney injury in pregnancy merits special attention because it involves risk to two lives. Renal insufficiency in pregnancy is mostly due to prerenal and ischemic causes, but can be due to specific pregnancy disorders.[1011] Worldwide, the incidence of AKI in pregnancy has decreased over the last 50 years. The observed decrease in the incidence of PR-AKI is mainly because of reduction in septic abortions after the legalization of abortion in most developed countries; and improved antenatal care; including prevention of uterine hemorrhage and early diagnosis and treatment of classic maternal complications of pregnancy like preeclampsia.[8] Stratta et al. reported that PR-AKI constituted 5.7% of total AKI cases over a cumulative period of 37 years.[7] They observed that in four successive periods (1956–1967, 1968–1977, 1978–1987, 1988–1994), the incidence of PR-AKI fell from 43% to 0.5% with respect to the total number of AKI, and from 1/3000 to 1/18,000 with respect to the total number of pregnancies.[7] Currently, the reported incidence of PR-AKI is 1 in 20,000 pregnancies in the developed countries.[57] Thus, PR-AKI is “a disappearing clinical entity” in the west.[7] Unfortunately, the incidence of PR-AKI in developing countries is still high though it has been decreasing in the past few years. Chugh et al. in 1970's reported that PR-AKI was responsible for 22.1% of patients undergoing dialysis over an 11 year period[2] and PR-AKI accounted for 15% of the total cases of AKI in 1987 from the same center.[12] A study from Pakistan reports a much higher incidence (36%) of PR-AKI.[13] Thus, AKI in pregnancy constituted 15–25% of total cases of AKI in the 1970's and 1980's; and septic abortion was the most common cause.[123]

Since 1980's, PR-AKI has decreased, and obstetrical cases constitute 9–13% of total AKI cases.[89] We have reported that the prevalence of PR-AKI among all cases of AKI decreased from 15% in 1980's to 10% in 1990's.[8] Similarly, PR-AKI was observed in 13.9% of total cases of AKI in our previous study.[14] The present study also reports a decrease in the incidence of PR-AKI with respect to the total cases of AKI from 15.2% in 1982–1991 to 4.68% in 2003–2014. This might be due to decreasing in the number of septic abortions, better antenatal and perinatal care, and early identification and management of specific pregnancy complications like preeclampsia. Despite declining trends, PR-AKI still accounts for 4–15% of total AKI cases in different parts of the country.[151617181920] We observed that postabortal sepsis is the most common cause of PR-AKI, followed by preeclampsia and puerperal sepsis. However, the proportion of AKI cases related to septic abortion has decreased in recent years in our country as well. In the Chandigarh study, AKI due to septic abortion was reported to decline to 3.5% in 1981–1986 from 13.7% of total AKI cases during 1965–1974.[21] In our previous study, we reported that postabortal AKI decreased to 7% in 1992–2002 from 9% of total AKI cases in 1982–1991.[8] In the present study, septic abortion contributed to 1.49% of total AKI cases in 2003–2014. The studies from other Indian centers report postabortal sepsis to be causal in <10% cases of PR-AKI.[1517] Thus, septic abortion-related AKI is declining in India, except in Kashmir valley, where 50% of total obstetric AKI was reported to be due to septic abortion.[18] This might to be due to regional differences in abortion practices and social stigma attached to abortion. Certain social factors may contribute to the high incidence of postabortal AKI because women from certain parts of the country seek an unsafe abortion, mostly conducted by untrained dais and midwives, despite the legalization of abortion in our country.[18] However, we observed a significant decrease in the percentage of patients with early pregnancy AKI in the present study, which might be due to decreasing the incidence of postabortal AKI. However, the decrease in the incidence of postabortal AKI is not uniform throughout the country.[8151820] Hyperemesis gravidarum has been emphasized as an important cause of PR-AKI in the first trimester of pregnancy in western literature.[22] We did not see even a single case of AKI due to this condition over a period of 33 years in our study, possibly due to under reporting or mild degree of AKI (prerenal azotemia) associated with hyperemesis gravidarum.

Figure 2 demonstrates that postabortal AKI is on the continuous decline, and the proportion of AKI occurring in the third trimester and postpartum period is continuously increasing. AKI in the third trimester of pregnancy occurred in 1.78% of total deliveries in our earlier study, and preeclampsia was the most common cause of third trimester AKI followed by puerperal sepsis.[10] In the developed countries, hypertensive complications of pregnancy, notably preeclampsia/HELLP syndrome and thrombotic microangiopathies are the major cause of PR-AKI, while preventable causes (sepsis and hemorrhage) are still leading causes of PR-AKI in developing countries.[16] Previous data from our country reported uterine hemorrhage (APH-PPH) to be the leading cause of PR-AKI, followed by sepsis.[2] Recent studies showed puerperal sepsis to be the most common cause, followed by hypertensive complications of pregnancy.[1517] We observed an increase in puerperal sepsis as a cause of PR-AKI in the last decade in our current study. This might indicates a need of specific interventions for prevention and treatment of sepsis and hypertensive complications of pregnancy, including encouragement of safe delivery practice. Studies from neighboring country Pakistan show APH-PPH to be still the most common causes of PR-AKI.[132324] In a study from South Indian center, Sivakumar et al. reported that 74.57% of the cases of PR-AKI occurred in the postpartum period, 16.94% in the third trimester, 6.77% in the second trimester, and 1.69% in the first trimester.[20] This highlights that PR-AKI occurs most commonly in the late third trimester and around delivery in both developing and developed countries but the etiologies differ. PE/HELLP and P-TMA are the most common causes of PR-AKI in developed countries. We have seen one case each of AFLP and aHUS causing AKI in the third trimester and postpartum period respectively. It is worth mentioning that pregnancy associated TMA (P-TMA) and AFLP are rare, affecting 1 per 25,000 and 1 per 7000–1 per 20,000 pregnancies respectively.[2526] Stratta et al. noted TMA (aHUS) in 2 (2.4%) patients in their series of 84 cases of PR-AKI over a period of 37 years.[7] In addition, to rare diseases, the inadequate investigation may account for under reporting of aHUS and AFLP as the cause of AKI in pregnant women in our country. Further, AFLP mimic with PR liver disease including viral hepatitis and biliary disease in pregnancy and their differential diagnosis may be difficult on the clinical ground. Thus, thrombotic microangioathy and AFLP are rare causes of PR-AKI in developing world. In contrast, puerperal sepsis and uterine hemorrhage are the major etiologies of PR-AKI in developing countries, in addition, to preeclampsia/HELLP syndrome.[151720] Preeclampsia was reported as the most common causes of PR-AKI in other Indian studies, as well.[1027] The reported frequency of AKI in preeclampsia varied between 24% and 35% from different centers in India.[101519] A striking observation in the present study was a significant decrease in the incidence of RCN from 17.7% in 1982–1991 to <2% in the subsequent two study periods. The decrease in the incidence of RCN is possibly due to the decreased incidence of septic abortion and APH-PPH, which is associated with the development of cortical necrosis in obstetrical renal failure.[12] The lower incidence of RCN in PR-AKI has been evident in the western world.[62829] The reported incidence of RCN in PR-AKI from our country in 1970's was high (26%).[2] In an earlier study from our center, we reported that the incidence of RCN in obstetric AKI was 23.8%.[30] However, the incidence of RCN decreased from 6.7% in 1984–1994 to 1.6% in 1995–2005 of total AKI cases.[9] However, the high incidence of cortical necrosis (20–25%) in obstetrical acute renal failure is still reported from other South Asian countries.[1324] We noted RCN in 1.44% of patients in 2003–2014. Diffuse and patchy cortical necrosis was seen in 1 and 3 cases, respectively of 4 patients of RCN in last 20 years (1992–2014). Thus, the both incidence and severity of RCN has decreased in patients with obstetric AKI.

The outcome of PR-AKI differs according to the period and place of study. Studies in 1970's era reported maternal mortality of 55%,[2] while recent studies report mortality to be ~15%, with complete recovery of renal functions in 42–75% cases and 8–30% patients landing in ESRD.[1517] We noted a decrease in maternal mortality from 20% in 1980's to 5.79% in 2003-2014. Perinatal mortality remained very high (~45%) throughout the study period mainly due to intrauterine death, stillbirth, and prematurity. Fetal mortality of 38.8% was reported in our previous study.[10] The high perinatal mortality ranging between 38% to 55% has been reported in other studies as well.[313233] All patients (100%) in our study, either had advance AKI or dialysis requiring AKI at the time of presentation. Hence, the question of missing mild AKI does not arise in the current study. The percentage of patients with PR-AKI needing RRT also decreased from 83% in 1982–1992 to 66.6% in 2003–2014. This might be due to early diagnosis and better nondialytic management of AKI. AKI in pregnancy may progress to ESRD in 10-30% of patients mainly due to RCN.[28] We have reported irreversible renal damage in 5.88% of patients in our previous study.[10] The incidence of irreversible renal damage was 11% (7/63) in a study from Italy and the risk was high when PE/E is complicated by abruption placentae (25%).[7] Maternal mortality in PR-AKI was 4.3% and 3.9% women remained dialysis dependent 4 months after delivery in a recent study from Canada.[34] Overall, 10.8% of cases with PR-AKI developed CKD in the present study. The number of patients with AKI in pregnancy progressing to ESRD has declined; from 6.15% in 1982–1991 to 1.4% in 2003–2014 and difference was statistically significant.

In summary, we observed a decreasing incidence of PR-AKI over the last three decades, particularly due to decreased postabortal AKI. We noted preeclampsia and puerperal sepsis were common causes of AKI in pregnancy in the third trimester and the postpartum period; both are treatable and preventable etiologies. The timely and aggressive management of APH/PPH have reduced AKI related to obstetrical hemorrhage. Pregnancy specific diseases such as P-HUS and AFLP are a rare cause of PR-AKI in developing countries. Safe practices of abortion, avoidance of unwanted pregnancy and improved antenatal and perinatal care, with special emphasis on safe and sterile delivery practices are necessary for a further decrease in the incidence of obstetric AKI. Despite decreasing the incidence of PR-AKI, fetal mortality remained very high. The development of CKD and ESRD has decreased in patient of PR-AKI in last decade in our study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This article is dedicated to my mentor and supervisor Prof. Pramod K. Srivastava, MD, DCH, former Professor of Medicine, Department of Medicine, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, 221005, India (Uttar Pradesh).

References

- Is pregnancy-related acute renal failure a disappearing clinical entity? Ren Fail. 1996;18:575-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure in pregnancy in a developing country: twenty years of experience. Ren Fail. 2006;28:309-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Decreasing incidence of renal cortical necrosis in patients with acute renal failure in developing countries: a single-centre experience of 22 years from Eastern India. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1213-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute kidney injury in late pregnancy in developing countries. Ren Fail. 2010;32:309-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Etiopathogenesis of acute renal failure in the tropics. Ann Natl Acad Med Sci. 1987;23:88-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure in pregnancy: one year observational study at Liaquat University Hospital, Hyderabad. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58:61-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure in pregnancy: Tertiary centre experience from north Indian population. Niger Med J. 2013;54:191-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute kidney injury in pregnancy-current status. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013;20:215-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure in pregnancy: our experience. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2014;25:450-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy related acute kidney injury: A single center experience from the Kashmir Valley. Indian J Nephrol. 2008;18:159-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy-related acute renal failure: a ten-year experience. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2011;22:352-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changing trends in acute renal failure in third-world countries – Chandigarh study. Q J Med. 1989;73:1117-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure in association with severe hyperemesis gravidarum. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(5 Pt 2):1119-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Etiology and outcome of acute renal failure in pregnancy. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2009;19:714-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Obstetrical acute renal failure: a challenging medical complication. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2011;23:66-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy-associated thrombocytopenia: definition, incidence and natural history. Acta Haematol. 1990;84:24-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- UK Obstetric Surveillance System. A prospective national study of acute fatty liver of pregnancy in the UK. Gut. 2008;57:951-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changing trends in pregnancy related acute renal failure. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2002;52:36-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spectrum of renal cortical necrosis in acute renal failure in eastern India. Postgrad Med J. 1995;71:208-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure complicating severe preeclampsia requiring admission to an obstetric intensive care unit. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:253-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics and Outcomes of AKI Treated with Dialysis during Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015 pii: ASN.2014100954

- [Google Scholar]