Translate this page into:

Collapsing glomerulopathy associated with pulmonary tuberculosis

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Collapsing glomerulopathy (CG) usually presents with reduced glomerular filtration rate, heavy proteinuria and has unfavorable prognosis. Numerous associations with CG are found. We encountered a case of CG associated with pulmonary tuberculosis presenting with proteinuria and dialysis-requiring severe renal failure. Our patient made partial recovery of his renal function and became dialysis-independent after antituberculous therapy and oral steroids. Long-term follow-up is needed to assess the progression of the disease.

Keywords

Collapsing glomerulopathy

heavy proteinuria

pulmonary tuberculosis

renal failure

Introduction

Collapsing glomerulopathy (CG) is being increasingly recognized as a cause of end-stage renal disease.[12] It is currently classified as one of the pathological variants of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS).[3] The exact cause of this lesion is still not known, but the list of associated genetic and acquired diseases has been growing.[124] CG is characterized by focal to diffuse, segmental to global, implosive collapse of the glomerular capillary tufts associated with marked proliferation and swelling of overlying podocytes resulting in the formation of pseudo crescents on light microscopy.[125] Immunofluorescence study is usually negative or shows only focal segmental positivity of immunoglobulin M (IgM), C3 and occasionally C1q. Electron microscopy shows collapse and wrinkling of glomerular basement membrane (GBM) and greatly hypertrophied overlying podocytes with diffuse foot process effacement. It usually manifests as heavy proteinuria with significant renal impairment.[5] CG associated with certain infections such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 infection, parvovirus B19, cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, human T-cell lymphotropic virus-1, hepatitis C virus (HCV), Leishmaniasis and Febrile illness has been documented.[124] One such rare association is with tuberculosis (TB).[67] To our knowledge, only three cases have been reported so far.

Case Report

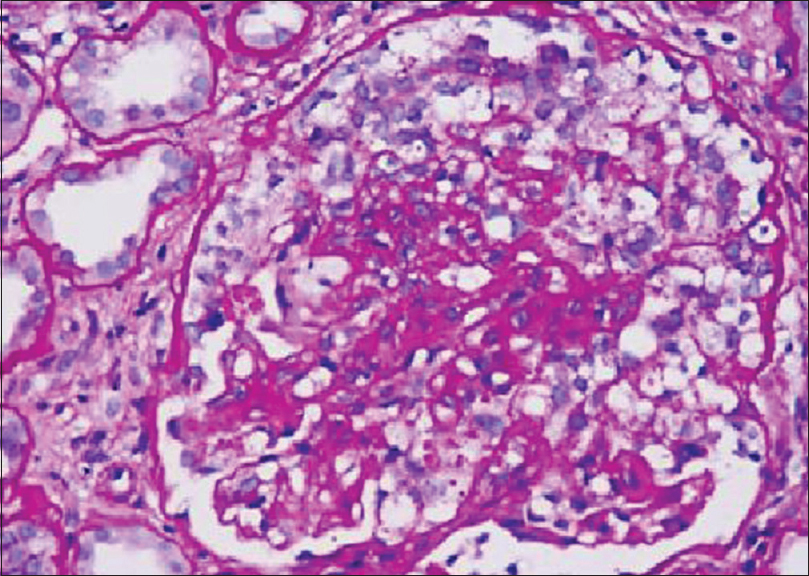

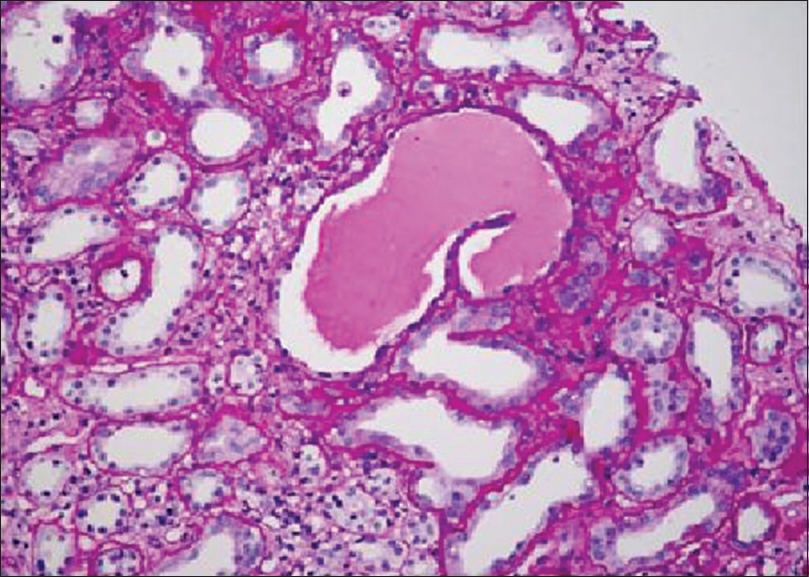

A 40-year-old man with diabetes and hypertension for 5 years presented with prolonged fever, cough and hemoptysis for 6 weeks duration and anasarca with breathlessness and oliguria (urine output <200 ml/day) of 2 weeks duration. He denied smoking, alcohol consumption and intravenous (IV) drug abuse. On clinical examination, he was febrile, pale, edematous, tachypneic (respiration rate – 26/min), tachycardic (pulse rate – 104 bpm) and hypertensive (blood pressure – 160/100 mmHg) with absent diabetic retinopathy. He had few crepitations and cavernous type of bronchial breath sounds in the infraclavicular and axillary region of the right lung. Rest of the systemic examination was normal. Urine analysis showed protein 3+, blood 3+ and pus cells 1-2/hpf. Twenty-four hours urine protein was 7.6 g/day. Complete blood count revealed a total white cell count of 10400/mm3 (polymorphs 58%, lymphocytes 36%, others 6%), hemoglobin of 8.3 g/dl and a platelet count of 3.69 lakhs/mm3. Peripheral smear showed microcytic hypochromic anemia with normal white cells and platelets. Serum urea was 124 mg/dl, and creatinine was 6.4 mg/dl. His fasting lipid profile was deranged with elevated total cholesterol (369 mg/dl) and triglyceride (542 mg/dl). Liver tests showed normal bilirubin and transaminase levels with low total protein (4.9 g/dl) and albumin (2.0 g/dl) levels. Serologies for hepatitis B virus, HCV, and HIV were negative. Anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies, anti-GBM antibody tests were negative. CMV DNA polymerase chain reaction test was negative. X-ray chest showed right apical cavity with consolidation. Two of the three sputum examinations for acid-fast bacilli were positive. After stabilizing him with three hemodialysis sessions, renal biopsy was performed. On light microscopy, 6 out of 9 glomeruli showed the collapse of capillary tuft with florid hyperplasia of the overlying podocytes [Figure 1]. Tubular epithelial cells showed signs of acute injury, interstitial edema with inflammatory cell infiltrate. Few of the tubules were dilated and contained proteinaceous casts [Figure 2]. Arteriolar hyalinosis was observed. No interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy were noted. Immunofluorescence microscopy was negative for antisera to IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q, kappa, and lambda light chains.

- This glomerulus shows collapse of the capillary tuft and prominent podocyte proliferation. Some podocytes contain protein resorption droplets, a common finding in collapsing lesion (PAS, ×400)

- Occasional microcystically dilated tubules containing proteinaceous casts were seen in the edematous interstitium (PAS, × 200)

Discussion

CG is an increasingly recognized morphological variant of FSGS. Association of CG with infections is well known. So far only a few cases of CG associated with pulmonary TB have been reported.[67]

Our patient presented with nephrotic proteinuria, severe renal failure, and sputum positive pulmonary TB. The absence of lambda and kappa light chains in the immunofluorescence of renal biopsy and normal serum protein electrophoretic pattern ruled out multiple myeloma. Our patient did not receive drugs such as interferon or pamidronate. Hence, after excluding all other possible causes, we surmise that the most probable cause of CG in our patient could be pulmonary TB. At present, no test is available to prove TB as the cause of CG.

Immune dysregulation secondary to infections may contribute to CG. Disturbance in the immune system, coupled with genetic susceptibility, likely contribute to the changes in glomerulus.[12] Coventry and Shoemaker reported a case of CG in a 16-year-old girl who presented with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome and pulmonary TB. In the absence of the usual associations (adult age group, African-American race, or history of IV drug abuse), infection was the sole known risk factor in that case. This lends support to the hypothesis that immune dysregulation due to infection per se, rather than infection by specific viral agents, may lead to CG in susceptible individuals.[6]

Rodrigues et al. reported an HIV-negative patient with TB-related CG who needed dialysis for 5 months but presented full renal recovery after TB treatment and corticotherapy.[7]

Light microscopy picture of our patient showed podocyte hyperplasia with the collapse of glomerular tuft. He also had features of acute tubular injury. Cases reported in the literature[67] also showed classical CG similar to our case.

Currently, there is no specific treatment for CG. The therapeutic approaches empirical and analogous to those used for noncollapsing FSGS, i.e., use of steroids or immunosuppressive agents.[125] Our patient was started on category I anti-tuberculous treatment (ATT) as per directly observed treatment strategy and oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day. He has completed 3 months ATT. We stopped oral steroids after tapering at the end of 2 months as his blood sugars became uncontrollable with insulin. He became sputum negative for mycobacterium TB and dialysis-independent at the end of 2 months. His serum creatinine and 24 h urine protein were 3.4 mg/dl and 2 g/day during the last follow-up. Long-term follow-up is needed to assess the progression of renal disease in this patient.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Anila Abraham Kurien, Director, Renopath, Center for Renal and Urological Pathology Pvt Ltd, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India.

References

- Pathologic classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: A working proposal. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:368-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Collapsing glomerulopathy in systemic autoimmune disorders: A case occurring in the course of full blown systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:277-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Collapsing glomerulopathy in a 16-year-old girl with pulmonary tuberculosis: The role of systemic inflammatory mediators. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2004;7:166-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tuberculosis-associated collapsing glomerulopathy: Remission after treatment. Ren Fail. 2010;32:143-6.

- [Google Scholar]