Translate this page into:

Measured Glomerular Filtration Rate at Dialysis Initiation and Clinical Outcomes of Indian Peritoneal Dialysis Patients

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

The optimal time for dialysis initiation remains controversial. Studies have failed to show better outcomes with early initiation of hemodialysis; even a few had shown increased adverse outcomes including poorer survival. Few studies have examined the same in patients on peritoneal dialysis (PD). Measured glomerular filtration rate (mGFR) not creatinine-based estimated GFR is recommended as the measure of kidney function in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients. The objective of this observational study was to compare the outcomes of Indian patients initiated on PD with different residual renal function (RRF) as measured by 24-h urinary clearance method. A total of 352 incident patients starting on chronic ambulatory PD as the first modality of renal replacement therapy were followed prospectively. Patients were categorized into three groups as per mGFR at the initiation of PD (≤5, >5–10, and >10 ml/min/1.73 m2). Patient survival and technique survival were compared among the three groups. Patients with GFR of ≤5 ml/min/1.73 m2 (hazard ratio [HR] - 3.42, 95% confidence interval [CI] - 1.85–6.30, P = 0.000) and >5–10 ml/min/1.73 m2 (HR - 2.16, 95% CI - 1.26–3.71, P = 0.005) had higher risk of mortality as compared to those with GFR of >10 ml/min/1.73 m2. Each increment of 1 ml/min/1.73 m2 in baseline GFR was associated with 10% reduced risk of death (HR - 0.90, 95% CI - 0.85–0.96, P = 0.002). Technique survival was poor in those with an initial mGFR of ≤5 ml/min/1.73 m2 as compared to other categories. RRF at the initiation was also an important factor predicting nutritional status at 1 year of follow-up. To conclude, initiation of PD at a lower baseline mGFR is associated with poorer patient and technique survival in Indian ESRD patients.

Keywords

Glomerular filtration rate

outcomes

peritoneal dialysis

Introduction

Chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD or PD) has been an established modality of renal replacement therapy for >2 decades in India. As with hemodialysis (HD), there is considerable variation in time of initiation of PD across the world and there has been a trend of initiating dialysis at higher estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) values.[1] Residual renal function (RRF) at initiation of dialysis is an important predictor of the clinical outcomes.[2] Most studies of HD have shown an association between early dialysis initiation and increased mortality, but a few studies have examined the same in PD patients.[3] The current evidence against early start of PD is not strong.[345] Majority of the Indian patients have multiple comorbidities and are malnourished at the start of PD, hence may have poorer long-term outcomes when dialysis therapy is started late.[6] Most recent guidelines recommend measured GFR (mGFR) instead of creatinine-based eGFR equations as the measure of RRF in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients.[789] The objective of this prospective study is to analyze the association of mGFR at dialysis initiation on various clinical outcomes of Indian CAPD patients.

Materials and Methods

Study design and study population

A total of 394 patients initiated on CAPD as an initial modality of RRT between December 2006 and December 2010 were included in this observational cohort study. We excluded patients with an age of < 18 years. Decision to initiate RRT was based on symptomatic uremia or refractory complications. Choice of dialysis modality, dialysis prescription, and follow-up management was not influenced by the study and was at discretion of treating physician.

Data collection and follow-up

The clinical and laboratory data were collected at dialysis initiation and then prospectively at 1 month, 3 months, and thereafter at every 6 month intervals. Baseline clinical data included age, sex, body mass index, diabetic status, underlying renal disease, and existing comorbidities. Comorbidity score was calculated as described by Davies comorbidity scoring system which is already validated in PD patients.[10] Nutritional status was assessed by anthropometry, 72-h dietary record, serum albumin level, and subjective global assessment (7-point SGA score).[11] Clearance studies and peritoneal equilibration test were performed at 1–2 months of PD initiation. Adequacy was measured by total weekly Kt/Vurea and total weekly creatinine clearance (CrCl) along with their peritoneal and renal components by PD Adequest 2.0 software (Baxter, Inc., Deerfield, IL, USA).[12] mGFR was calculated as an average of 24-h urinary urea and CrCl at initiation of dialysis. Patients were categorized into three groups based on mGFR as follows: Group 1 with GFR ≤5 ml/min/1.73 m2 (n = 92), Group 2 with GFR between >5 and 10 ml/min/1.73 m2 (n = 146), and Group 3 with GFR >10 ml/min/1.73 m2 (n = 114). The stratification was based on cutoffs suggested in most guidelines and previous studies.[7813]

Study endpoints

Patients were prospectively followed until death, renal transplantation, technique failure, or the end of the study (December 2014). The outcomes of interest were all-cause mortality and technique failure. Secondary outcome was change in nutritional status (i.e. serum albumin and SGA score) of the patients after 1 year of dialysis. Technique failure was defined as removal of PD catheter and permanent transfer to hemodialysis due to any reason. For patients having a change in modality, censoring of patients was done at 1 month after PD to HD switch.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for continuous data and as percentages for categorical data. Baseline clinical, nutritional, and adequacy data among the three groups were compared by Chi-square test or analysis of variance as appropriate. Follow-up nutritional parameters were compared with initial values using paired Student's t-tests for individual groups. Due to skewed distribution, Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare number of peritonitis episodes and days of hospitalization among groups. Kaplan–Meier analysis was done for patient survival and technique survival, and the log-rank test was used to compare the significance between the groups. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards model were used to analyze factors predicting mortality and technique failure and estimate adjusted hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). A P = 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was done with SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, and informed consent was obtained from all patient or their relatives. The study was performed as per the ethical standards laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

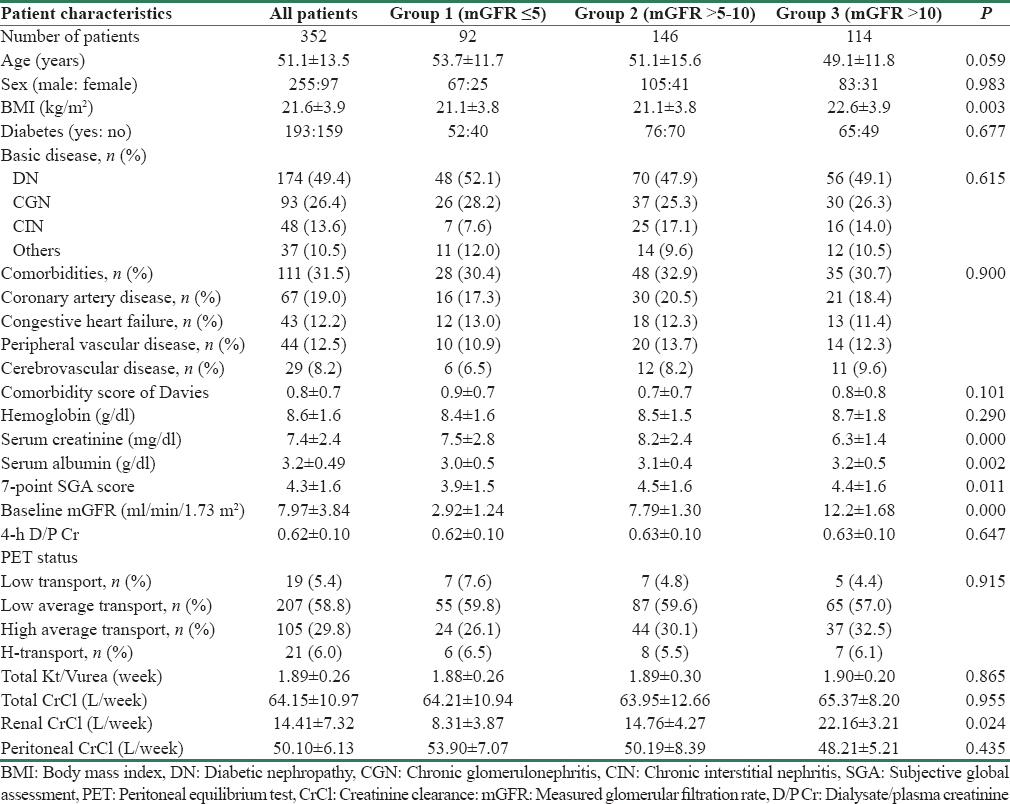

Of the 394 patients, 6 patients did not consent for the study, 15 patients discontinued dialysis within 1 month, 9 patients lost to follow-up within 3 months, and 12 patients died within 3 months of dialysis initiation. Thus, remaining 352 patients were included in the study. Baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Diabetic nephropathy (174/352, 49.4%) followed by chronic glomerulonephritis (93/352, 26.4%) was the most common cause of ESRD. Of 352 patients, 111 patients (31.5%) had one or more comorbid condition at dialysis initiation; however, patients in all the three groups had similar comorbidity scores (P = 0.101). As assigned, the three groups had significant difference of mGFR between them. An average GFR difference of 10.6 and 4.4 ml/min/1.73 m2 was present between Group 3 and Group 2 as compared to Group 1, respectively. Patients in all three groups were similar in terms of adequacy of dialysis (i.e. weekly total Kt/Vurea and total CrCl).

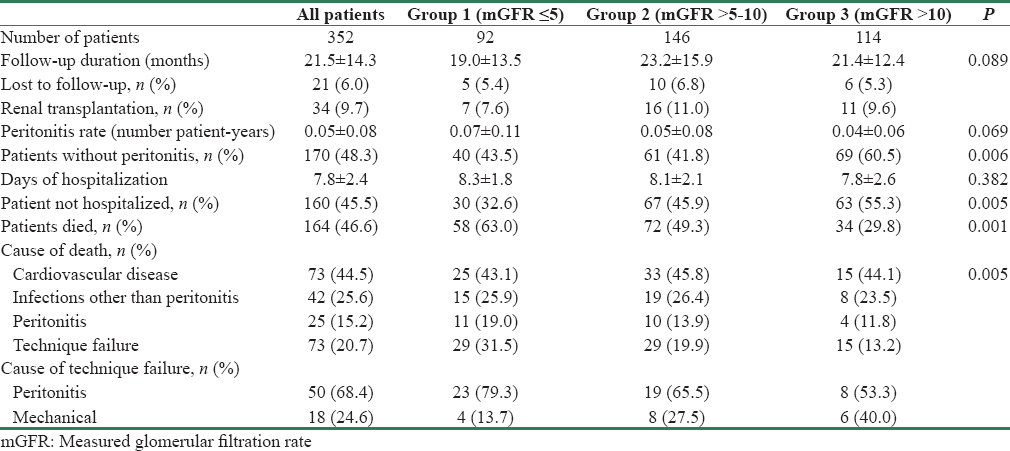

Peritonitis, hospitalization, and outcome data are shown in Table 2. During the follow-up period (mean 21.5 ± 14.3 months), there were 254 episodes of peritonitis in 182 patients with overall peritonitis rate being 0.05 ± 0.08 episodes per patient-year. Of 352 patients, 170 (48.3%) patients were peritonitis-free on follow-up. Higher proportion of patients in Group 3 with greater residual GFR was peritonitis-free on follow-up (P = 0.006). There were 1486 days of hospitalization in 192 patients; average duration of hospitalization was 7.8 ± 2.4 days per patient per year. Of 352 patients, 160 (45.5%) patients were never hospitalized. Group 3 patients were less likely to require hospitalization as compared to other groups (P = 0.005).

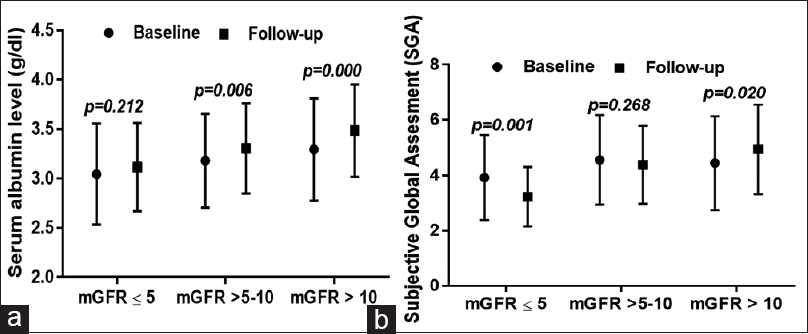

On follow-up at 1 year, serum albumin levels increased significantly in Group 2 (3.18 ± 0.47 vs. 3.30 ± 0.45, P = 0.006) and Group 3 (3.29 ± 0.51 vs. 3.48 ± 0.46, P = 0.000) but remained similar in Group 1 (3.04 ± 0.51 vs. 3.11 ± 0.44, P = 0.212) [Figure 1a]. Mean SGA score decreased in Group 1 (3.9 ± 1.5 vs. 3.2 ± 1.0, P = 0.001) and remained same in Group 2 (4.5 ± 1.6 vs. 4.3 ± 1.4, P = 0.268), but there was a significant increase in Group 3 (4.4 ± 1.7 vs. 4.9 ± 1.6, P = 0.020) [Figure 1b].

- (a) Changes in serum albumin level at baseline and 1 year of follow-up in three different categories at initiation of peritoneal dialysis. (b) Changes in subjective global assessment score at baseline and 1 year of follow-up in three different categories of glomerular filtration rate at initiation of peritoneal dialysis

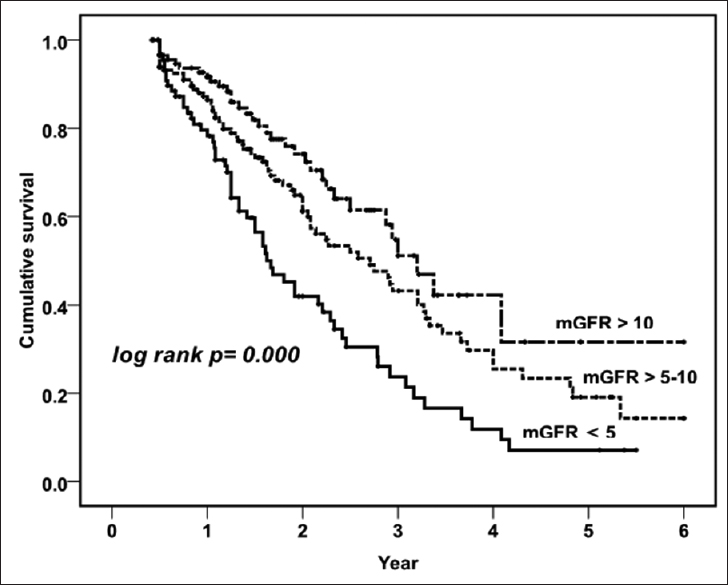

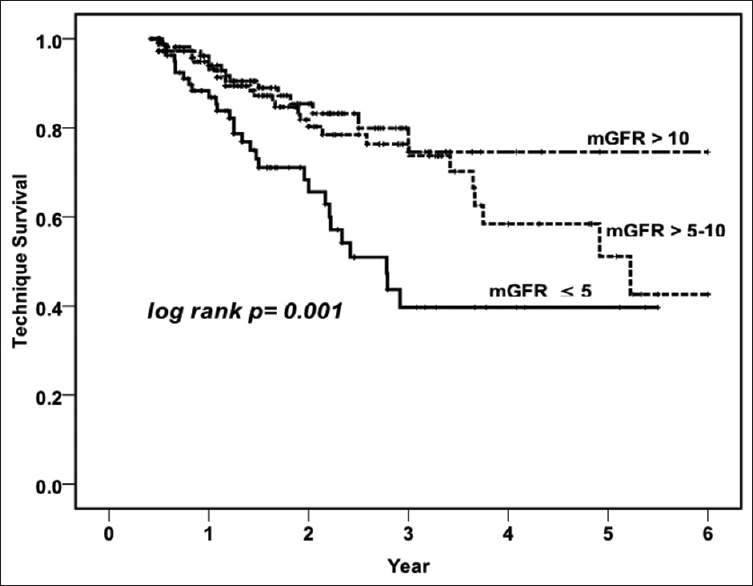

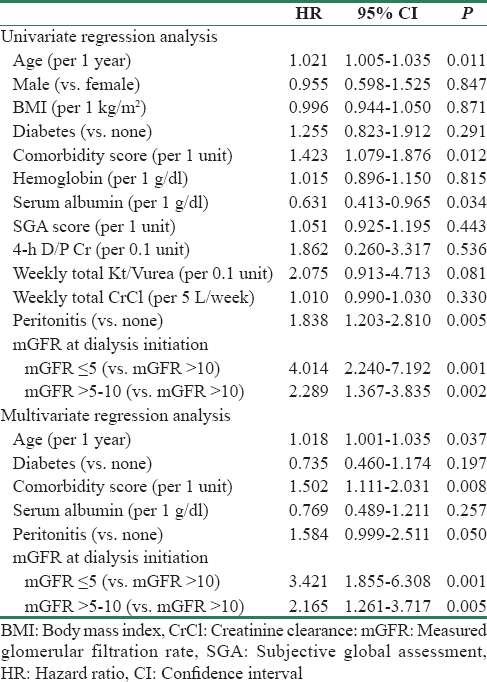

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis revealed that patient survival [Figure 2, log rank P = 0.000] and technique survival [Figure 3, log rank P = 0.001] were better in higher baseline GFR groups. The 1-, 2-, 3-, and 5-year patient survival in patients with Group 1 were 78.2%, 41.9%, 24.8%, and 7.8%; Group 2 were 87.2%, 64.8%, 43.1%, and 19.1%; and Group 3 were 91.6%, 74.1%, 51.1%, and 20.2%; respectively. Along with baseline mGFR (for each increment of 1 ml/min/1.73 m2 of mGFR; HR - 0.90, 95% CI - 0.85–0.96, P = 0.002), age, comorbidity score, and peritonitis were significantly associated with mortality on Cox regression analysis [Table 3]. Compared to Group 3, both Group 1 (HR - 3.42, 95% CI - 1.85–6.30, P = 0.000) and Group 2 (HR - 2.16, 95% CI - 1.26–3.71, P = 0.005) had higher risk of mortality in the adjusted model. The technique survival of patients at 1, 2, 3, and 5 years in Group 1 was 88.3%, 68.3%, 39.7%, and 16.1%; Group 2 was 94.9%, 81.8%, 73.7%, and 51.1%; and Group 3 was 94.0%, 83.2%, 74.6%, and 31.4%, respectively. In a multivariate analysis for technique survival, initial mGFR of ≤5 ml/min/1.73 m2 was significant risk factor for discontinuation of PD as compared to others (Group 1 vs. Group 3; HR - 3.42, 95% CI - 1.63–7.15, P = 0.001 and Group 1 vs. Group 2; HR - 2.83, 95% CI - 1.83–4.33, P = 0.004).

- Kaplan–Meier survival curve showing patient survival in three different categories of glomerular filtration rate

- Kaplan–Meier survival curve showing technique survival in three different categories of glomerular filtration rate

Discussion

In this study, we observed that lower mGFR at PD initiation was associated with poorer patient survival rates after adjustment for age, diabetes, comorbidities, and peritonitis episode. Patients with mGFR of ≤5 ml/min/1.73 m2 had 3.4 times and patients with initial mGFR of >5–10 ml/min/1.73 m2 had 2.1 times risk of death compared to patients with mGFR of >10 ml/min/1.73 m2 at dialysis initiation. Each increment of 1 ml/min/1.73 m2 in baseline mGFR was associated with 10% reduced risk of death. Our findings are similar with results of the CANUSA and Hong Kong PD Study.[1415] It has been shown that renal contribution to solute clearance is more important than peritoneal clearance and anuric patients have higher mortality rates.[16] It had been postulated that early initiation of dialysis will have less uremic complications, better volume status, and hence, fewer hospitalization and less mortality.[2] In our cohort, death-censored technique survival was poor in patients with mGFR of ≤5 ml/min/1.73 m2 at PD initiation. Although peritonitis rates were comparable between the groups in our study, proportion of the patients with higher GFR were more likely to be peritonitis-free and had less chances of hospitalization, which may have translated into higher technique survival rates in these groups. Similar to this study, other studies have shown that RRF at initiation of dialysis is an important factor predicting nutritional status of patients both at baseline and on follow-up.[17] It has also been shown that malnutrition was associated with higher peritonitis rate, technique failure, and mortality.[18] We have previously shown the confounding effect of comorbidities and malnutrition on survival of PD patients, patients with comorbidity and malnutrition both had highest risk of mortality, and majority of patients were malnourished at the beginning of dialysis initiation.[6] In the present study, we had included comorbidity and nutritional parameters in adjusted model as they are important determinants of mortality.

Retrospective studies have shown that an early start of dialysis had no beneficial effect or even had worse outcomes.[319] These data have been a point of debate for long, and several caveats need to be underscored when drawing conclusions.[20] First, evidence against early start of dialysis is more robust for HD than in PD.[3] HD was the predominant modality of dialysis (proportion of patients on PD was only 3%–10%) in the studies that found higher risk of mortality with earlier initiation.[3] HD is associated with faster loss of RRF, ventricular arrhythmias, and increased exposure to vascular catheters, which may explain higher mortality as compared to PD.[21] Meta-analysis restricted to PD patients has found no association of GFR with mortality.[3] Initiating Dialysis Early and Late study, the only randomized controlled study till date, found no survival benefit of early dialysis initiation (10–14 ml/min/1.73 m2) compared to late initiation (5–7 ml/min/1.73 m2).[4] However, 76% of the patients in the late-start group had to initiate dialysis early due to uremia and only 6% had significant comorbidities. Of note, the mean GFR difference between the groups was only 1.8 ml/min/1.73 m2, possibly too small to detect any survival benefit. Results were similar in a subgroup analysis of the 349 patients in the study who were initiated on PD.[22] Recently, a large (n = 8047) Canadian registry analysis involving only PD found no association of increased mortality with earlier initiation.[5] Second, the presence of comorbidity and malnutrition is important determinant of outcomes. This may influence the results of the studies as these patients usually start dialysis earlier and also have more probability of death.[2324] Finally, studies that found higher mortality risk with earlier dialysis initiation have used one of the eGFR equations; however, studies that measured kidney function from 24-h urine collection (mGFR) found lower mortality with the same.[3] In one study, higher eGFR but not higher mGFR showed an association with poorer survival.[25] It has been shown that is such cases higher GFR is commonly due to lower creatinine production, resulting from reduced muscle mass rather than better RRF.[26]

The major strength of our study is that it is the first prospective study comparing baseline mGFR in Indian cohort and all patients were started on CAPD from the beginning, except few sessions of HD before initiation (i.e. during break-in period). Instead of an eGFR equation, we have used average of 24-h urinary urea and CrCl to measure RRF which has been recommended by most recent guidelines.[789] Any eGFR equation would have overestimated RRF in Indian ESRD patients as they have greater degree of muscle wasting and hence may have confounded the results by misclassifying patients to a higher GFR group. Finally, the present study had a remarkable difference of GFR between the groups so as to detect any survival advantage.

Although many predialysis covariates were considered, the study carries important limitations as we did not measure rate of decline of GFR during follow-up, which may have influenced the outcomes and the sample size of the study is small in each group, which limits the power of the study. Considering the current evidence including our study, it can be proposed that earlier initiation of PD may have better outcomes as compared to late initiation group. This has important implication in asymptomatic patients as earlier PD initiation with incremental dialysis may provide the best mode of transition from conservative management avoiding adverse outcomes associated with HD initiation while not affecting quality of life.[27] A controlled study comparing either modality of dialysis with an incremental dosing protocol for both may answer the question conclusively.

Conclusion

The initiation of CAPD at a lower baseline mGFR is associated with poorer patient and technique survival in Indian ESRD patients. The patients with higher RRF at PD initiation have better nutritional status on follow-up.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- The importance of residual kidney function for patients on dialysis: A critical review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:1068-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- GFR at initiation of dialysis and mortality in CKD: A meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59:829-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- A randomized, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:609-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Timing of peritoneal dialysis initiation and mortality: Analysis of the Canadian Organ Replacement Registry. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:798-805.

- [Google Scholar]

- Confounding effect of comorbidities and malnutrition on survival of peritoneal dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2010;20:384-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- When to start dialysis: Updated guidance following publication of the Initiating Dialysis Early and Late (IDEAL) study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2082-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Japanese society for dialysis therapy clinical guideline for “hemodialysis initiation for maintenance hemodialysis”. Ther Apher Dial. 2015;19(Suppl 1):93-107.

- [Google Scholar]

- ISPD Cardiovascular and metabolic guidelines in adult peritoneal dialysis patients part I-Assessment and management of various cardiovascular risk factors. Perit Dial Int. 2015;35:379-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantifying comorbidity in peritoneal dialysis patients and its relationship to other predictors of survival. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:1085-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adequacy of dialysis and nutrition in continuous peritoneal dialysis: Association with clinical outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:198-207.

- [Google Scholar]

- A multinational clinical validation study of PD ADEQUEST 2.0. PD ADEQUEST international study group. Perit Dial Int. 1999;19:556-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Society of Nephrology 2014 clinical practice guideline for timing the initiation of chronic dialysis. CMAJ. 2014;186:112-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relative contribution of residual renal function and peritoneal clearance to adequacy of dialysis: A reanalysis of the CANUSA study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2158-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delaying initiation of dialysis till symptomatic uraemia – Is it too late? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1926-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Full loss of residual renal function causes higher mortality in dialysis patients; findings from a marginal structural model. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2978-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changes in nutritional status on follow-up of an incident cohort of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2008;18:195-201.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reduced residual renal function is a risk of peritonitis in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:2653-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early initiation of dialysis and late implantation of catheters adversely affect outcomes of patients on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2008;28:73-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Timing of dialysis initiation in transplant-naive and failed transplant patients. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8:284-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between dialysis modality and mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:155-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of timing of dialysis commencement on clinical outcomes of patients with planned initiation of peritoneal dialysis in the IDEAL trial. Perit Dial Int. 2012;32:595-604.

- [Google Scholar]

- Age and comorbidity may explain the paradoxical association of an early dialysis start with poor survival. Kidney Int. 2010;77:700-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dialysis: Low-glucose-containing peritoneal dialysis solutions: Good or bad? Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:635-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The MDRD formula does not reflect GFR in ESRD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1932-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Creatinine production, nutrition, and glomerular filtration rate estimation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1000-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The intact nephron hypothesis in reverse: An argument to support incremental dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:1602-4.

- [Google Scholar]