Translate this page into:

Antenatal Bartter Syndrome Caused by a Novel Homozygous Mutation in SLC12A1 Gene

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Antenatal Bartter syndrome (BS) is an autosomal recessive hereditary renal tubular disorder caused by mutation in the solute carrier family 12 member 1 (SLC12A1) gene on chromosome 15q21.1. This syndrome is characterized by polyuria, hyponatremia, hypokalemic hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis, and hypercalciuria associated with increased urinary loss of electrolytes. Herein, we report a very low-birth-weight premature newborn with antenatal BS caused by a novel homozygous mutation in the SLC12A1 gene, c.596G>A (p.R199H).

Keywords

Antenatal Bartter syndrome

mutation

SLC12A1 gene

Introduction

Bartter syndrome (BS) is a rare hereditary kidney disorder characterized by hypokalemic hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis, salt wasting, polyuria, and normal blood pressure in spite of hyperreninemic hyperaldosteronism.[1] The overall incidence of BS is estimated to be 1.2/million population.[2] Pathophysiology of BS depends on defects of sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter-2 (NKCC2) and K+ and Cl− channels in thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle (TALH).[3] Early diagnosis and treatment of BS is important. Delayed diagnosis can lead to increased morbidity and mortality because of severe fluid–electrolyte losses. Herein, a very low-birth-weight premature newborn with antenatal BS having a novel homozygous mutation of c.596G>A (p.R199H) of the SLC12A1 gene is presented.

Case History

Case report

A female newborn was born by cesarean section with 1270 g (10th percentile) birth weight to non-consanguineous healthy parents at the 30th gestational week. Her length was 40 cm (50th percentile), head circumference 29 cm (50th percentile), and Apgar scores at the first and fifth minutes 6 and 7, respectively. Fetal ultrasonography revealed polyhydramnios. The first pregnancy of the mother was spontaneous abortion at seventh gestational week. Her elder sister was born at the 24th gestational week and died at the postnatal 36 h due to respiratory failure. Her younger sister was born at 29th gestational week and died when 3 years old because of severe fluid–electrolyte loss due to diarrhea. Polyhydramnios had been reported in all pregnancies.

Noninvasive mechanic ventilation support was given to our patient for respiratory distress. The polyuria (9 cm3/kg/h) was developed on the postnatal fourth day of life. Biochemical analyses showed that blood sodium level was 108 meq/L, potassium 2.2 meq/L, chloride 67 meq/L, calcium 7.5 mg/dL, magnesium 2.27 mg/dL, creatinine 0.79 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen 36 mg/dL, uric acid 8.2 mg/dL, urine chloride 41 meq/L, urine sodium 128 meq/L, and urine calcium: creatinine ratio was high (4.66 mg/mg). Arterial blood gas analysis revealed that pH was 7.46, pCO242.5 mmHg, HCO327.9 meq/L, and base excess 6.6 mmol/L. In spite of normal blood pressure, serum aldosterone level and plasma renin activity were elevated. Serum aldosterone level was 297 ng/dL (normal range: 5–90 ng/dL) and plasma renin activity was 36 ng/mL/h (normal range: <17.5 ng/mL/h). Appropriate fluid and electrolyte support was given to the patient to prevent hyponatremia, hypochloremia, hypokalemia, renal failure, and further weight loss. Sodium chloride and potassium requirements were up to 35 and 4 meq/kg/day during treatment, respectively.

Based on clinical and laboratory findings, the patient was diagnosed with BS and managed with indomethacin (1 mg/kg/day), fluid, and electrolyte supplementations. Also, she was closely followed up for side effects of indomethacin such as necrotizing enterocolitis and acute kidney injury. But no side effects of indomethacin were observed in the follow-up.

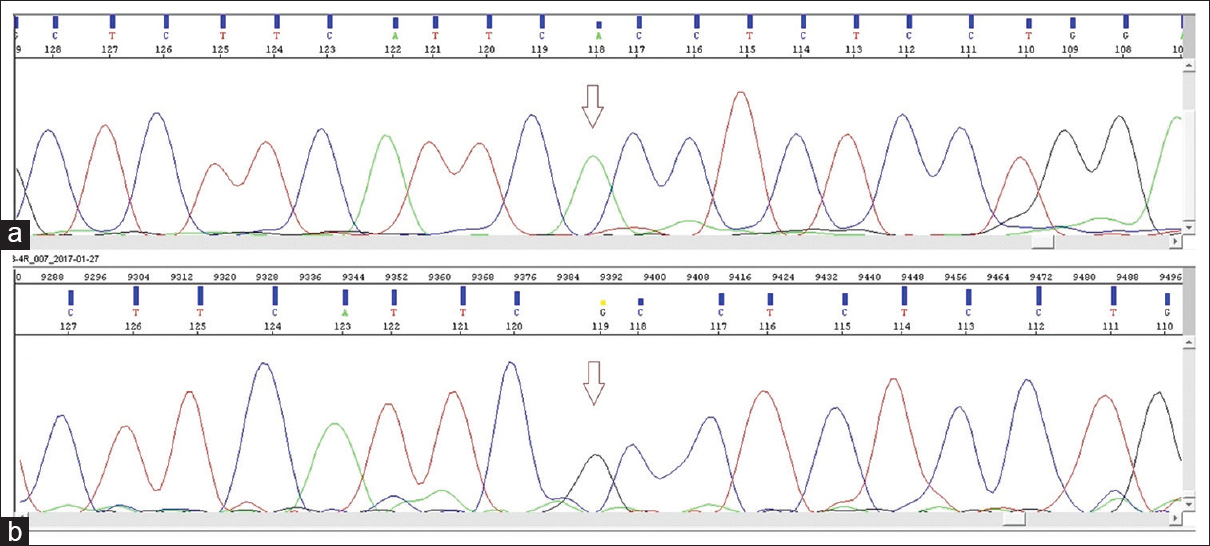

In our patient, the diagnosis of BS was confirmed by genetic analysis. DNA was extracted from peripheral blood, and exon and exon–intron junction areas of SLC12A1 gene (NM_001184832.1) were sequenced using next-generation sequencing method (MiSeq-Illumina). It revealed a novel homozygous NM_001184832.1 c.596G>A (p.R199H) mutation [Figure 1]. Her parents' genetic analysis revealed that they had heterozygous NM_001184832.1 c.596G>A (p.R199H) mutation. Genetic counseling was given to her parents.

- (a) Sequence chromatogram showing p.R199H (c.596G>A) splicing acceptor site mutation in SLC12A1 gene. Arrow shows the position of the substitution. (b) Sequence chromatogram showing normal sequence of SLC12A1 gene

She was discharged on postnatal fifth week of life with oral sodium, potassium, and indomethacin treatment (4 meq/kg/day, 2 meq/kg/day, and 1 mg/kg/day, respectively). Brainstem evoked response audiometry test was bilaterally positive. Although first renal ultrasonography examination was normal, medullary nephrocalcinosis was detected on control renal ultrasonography performed on the fifth month. Her growth, development, and renal function tests (RFT) [Table 1] were within normal limits of age due to early diagnosis, appropriate treatment of fluid–electrolyte and calorie support, and close follow-up.

| Parameters | Day 1 | Day 4 | Day 21 | Day 30 | Month 2 | Month 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum sodium (mmol/L) | 137 | 108 | 128 | 134 | 139 | 140 |

| Serum potassium (mmol/L) | 4.4 | 2.2 | 3.9 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.1 |

| Serum chloride (mmol/L) | 109 | 67 | 99 | 96 | 96 | 106 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | 9.6 | 7.5 | 9.1 | 9.6 | 9.9 | 10 |

| Serum magnesium (mg/dL) | 2.08 | 2.27 | 2 | 1.98 | 2.13 | 2.04 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.49 | 0.79 | 1.1 | 0.53 | 0.5 | 0.36 |

| Serum blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 6 | 36 | 13 | 16 | 0.28 | 9 |

| Serum uric acid (mg/dL) | 6.7 | 8.2 | 5.6 | 6.4 | 4.3 | 4.5 |

| Urine chloride (mmol/L) | - | 41 | - | - | - | - |

| Weight (g) and percentile | 1270 (25th p) | 1210 (25th p) | 1300 (3th p) | 1900 (10th p) | 2700 (10-25th p) | 5500 (10-25th p) |

RFT: Renal function test

Discussion

Bartter syndrome was first described by Federic Bartter in 1962.[4] It is classified into five types according to their underlying genetic defect.[125] Two distinct clinical phenotypes of BS are seen according to age of onset as antenatal BS and classic BS.[6] Types 1 and 2 BS also known as antenatal BS are inherited autosomal recessively, and clinically these are the most severe types. Type 2 BS is caused by mutations of the SLC12A1 gene, which encodes the NKCC2 channels in TALH.[7] The SLC12A1 gene has kidney-specific transcription and is located at 15q21.1.[17] Up to now, more than 70 mutations have been identified on this gene.[1] Type 2 BS is caused by mutations of the potassium inwardly rectifying channel subfamily J, member 1 (KCNJ1) gene located at 11q24.3, which encodes K+ channels in TALH.[8]

The diagnosis of antenatal BS type 1 in our patient was based on clinical and laboratory findings and confirmed by the presence of a new homozygous NM_001184832.1 c.596G>A (p.R199H) mutation.

Antenatal features of BS include polyhydramnios and premature delivery. There were polyhydramnios and premature birth history in all pregnancies of the mother. Clinical presentation of BS type 1 and 2 is almost similar with the exception of transient hyperkalemia, seen in BS type 2 during the first few days of life. The other clinical findings are polyhydramnios, premature birth, low-birth weight, polyuria, life-threatening dehydration, and nephrocalcinosis. Fetal polyuria causes polyhydramnios in the mother and results in preterm labor, as in our case. Because of unexplained polyhydramnios and premature birth history in all pregnancies of the mother, our patient was considered as having BS. But there is no definite diagnosis in sisters of our patient. There is also electrolyte imbalance due to defective absorption of sodium, chloride and potassium. Bartter syndrome should be considered if a neonate has polyhydramnios, preterm labor, polyuria, metabolic alkalosis, hyponatremia–hypokalemia, and normal blood pressure in spite of hyperreninemic hyperaldosteronism. In our case, all the findings defined above were detected. The diagnosis of antenatal BS in our patient was based on clinical and biochemical features and confirmed by the presence of a new mutation in SLC12A1 gene.

Management of antenatal BS includes appropriate fluid–electrolyte support and indomethacin treatment.[3] Patients with BS must be monitored for dehydration, electrolyte balance, and weight loss. Delay in diagnosis and treatment leads to rapidly renal failure. In initial years, the salt losses contribute to mortality. Acute kidney injury is usually due to prerenal factors or continuing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) during severe dehydration. The clinical course of antenatal BS may be different in patients. Usually, somatic growth is impaired in most infants with types 1, 2, and 4 BS. Neurodevelopment in patients with BS is usually not affected. Puricelli et al.[9] reported that both the neuro developmental outcome and the somatic growth in patients with BS were normal. Similarly, our patient's electrolytes, RFT, growth, and development were within normal limits of age due to early diagnosis, appropriate treatment of fluid–electrolyte, calorie support, and close follow-up. In addition to the cases diagnosed with antenatal BS in the intrauterine period, there are also cases diagnosed with antenatal BS in the late period.[10]

Indomethacin, a cyclooxygenase inhibitor, inhibits cyclooxgenase and reduces the prostaglandin synthesis and corrects electrolyte imbalance. Patients, especially premature infants, should be closely followed up for side effects such as necrotizing enterocolitis and acute kidney injury. Therefore, it is recommended that indomethacin should either not be used in premature infants or its use is delayed by perhaps 4–6 weeks after birth.[11] Most infants with antenatal BS are difficult to treat. Few infants may have a spontaneous improvement with reduction in salt and NSAID dose requirement. In our patient, indomethacin treatment was started at the age of 21 days, but no side effects of indomethacin were observed in the follow-up. Indomethacin was given to our patient in the early postpartum period because excessive supplementation of salt and water was necessary to prevent electrolytes and fluid imbalances. Roy et al.[10] reported a premature newborn diagnosed with BS who was started on indomethacin (2 mg/kg/day) at the age of 21 days, and no side effects of indomethacin were observed in the follow-up. Also, there are many reports like that our case in the literature using indomethacin before fourth week of life in premature infants.[1213]

Life-threatening dehydration and nephrocalcinosis can be seen in antenatal type 1 BS.[3] Nephrocalcinosis and electrolyte imbalance such as hypokalemia and hypercalciuria may cause chronic tubulointerstitial nephropathy.[14] Nephrocalcinosis can occur despite indomethacin treatment, whereas resolution of nephrocalcinosis can be seen during receiving indomethacin.[1516] Medullary nephrocalcinosis was detected at the fifth month of age in our case despite indomethacin treatment.

In summary, antenatal BS should be kept in mind especially in any newborn with antenatal history of unexplained polyhydramnios or postnatal polyuria, hyponatremia, and hypokalemic hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis. In patients with these clinical findings, genetic study to diagnose antenatal BS should be considered. Because of favorable effect on morbidity and mortality, early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of BS is crucial as seen in our case.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Genetic heterogeneity in patients withBartter syndrome type 1. Mol Med Rep. 2017;15:581-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular pathophysiology of Bartter's and Gitelman's syndromes. World J Pediatr. 2015;11:113-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hyperplasia of the juxtaglomerular complex with hyperaldosteronism and hypokalemic alkalosis. A new syndrome. Am J Med. 1962;33:811-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic basis of Bartter syndrome in Korea. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:1516-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel variant in the SLC12A1 gene in two families with antenatal Bartter syndrome. Acta Pediatr. 2017;106:161-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bartter's syndrome, hypokalaemic alkalosis with hypercalciuria, is caused by mutations in the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter NKCC2. Nat Genet. 1996;13:183-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic heterogeneity of Bartter's syndrome revealed by mutations in the K+ channel, ROMK. Nat Genet. 1996;14:152-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term follow-up of patients with Bartter syndrome type I and II. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:2976-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Late-onset manifestation of antenatal Bartter syndrome as a result of residual function of the mutated renal Na+-K+-2Cl- co-transporter. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2136-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nephrocalcinosis and placental findings in neonatal bartter syndrome. AJP Rep. 2013;3:21-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Disorders of renal tubular handling of sodium and potassium. In: MA Holliday, TM Barrott, BL Vernier, eds. Pediatric Nephrology (2nd ed). Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1987. p. :598-605.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bartter syndrome in neonate: Early treatment with Indomethacin. Paediatr Nephrol. 2000;14:143-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypercalciuric Bartter syndrome: Resolution of nephrocalcinosis with Indomethacin. AJR. 1989;152:1251-3.

- [Google Scholar]